Preservers and Propagators of Liberty as Teachers of the Human Race

By Stephen McDowell

This article is from, Stephen K. McDowell, Building Godly Nations

“Dear God, guide me. Make my life count,” prayed Susanna Wesley daily. Born the 25th of 25 children to a minister and his wife, she loved God from her youth and had a burning desire to live her life for Him. As a young woman she dreamed, “I hope the fire I start will not only burn all of London but all of the United K ingdom as well. I hope it will burn all over the world.”

ingdom as well. I hope it will burn all over the world.”

Susanna was always looking for an opportunity to fulfill that dream and was always asking God what He would have her do. How should she start that fire? Should she become a missionary, a teacher? Or did God have another plan for her? At a young age she married a minister and, like her mother, began having children —19 in all. She devoted most of her time and effort to being a good wife and mother.

Even in the midst of hardship after hardship, she continued to pour herself into her children and inspire them for good. When her children were around five or six-years-old she would set aside one whole day to teach them how to read. She taught the alphabet phonetically and then had her children read the Bible.

She never traveled throughout the world or directly started a spiritual fire in London or elsewhere. But Susanna’s dream did become a reality in her 13th and 17th born children, Charles and John Wesley, who spread the Gospel throughout the world.

Susanna Wesley’s words, “Dear God, guide me. Make my life count,” have echoed down through the centuries as women have tried to discern God’s role for them in the advancement of liberty, nations, and His Kingdom. Modern women can look to them as examples for applying Biblical principles to their lives as they strive to leave their own mark on history.

Molding Young Minds

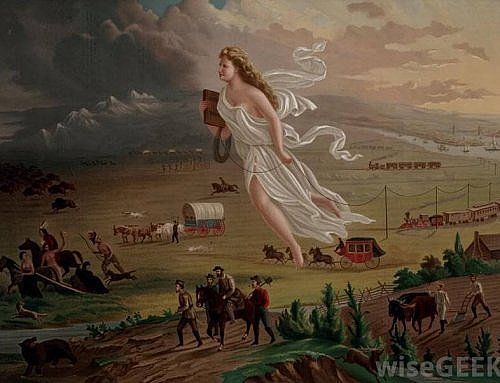

Women in early America saw their most crucial role in society as forming the character of the next generation. They thought that men, in general, could lead the nation, but that they were the ones who would train the leaders. This was primarily carried out in the home.

John Adams wrote in a letter to his wife, Abigail, “I think I have some times observed to you in conversation, that upon examining the biography of illustrious men, you will generally find some female about them, in the relation of mother, or wife, or sister, to whose instigation a great part of their merit is to be ascribed.”1

In recent years, people have debated whether women can compete with men in public life. Certainly they can, but never forget that no one can compete with a mother in the home. As more mothers have joined the workforce, through choice or necessity, the United States has experienced greater problems because those who can best form the character of the next generation are having less input into the lives of the next generation. Neither the state, nor the school, nor even the church can effectively replace mom or dad in the home.

Daniel Webster said it well in his Remarks to the Ladies of Richmond, October 5, 1840:

[T]he mothers of a civilized nation . . . [work], not on frail and perishable matter, but on the immortal mind, moulding and fashioning beings who are to exist for ever. . . . They work, not upon the canvas that shall perish, or the marble that shall crumble into dust, but upon mind, upon spirit, which is to last for ever, and which is to bear, for good or evil, throughout its duration, the impress of a mother’s . . . hand.2

God has ordained certain unique duties for men and women. The primary role of women is as mothers, who are teachers that form and shape the character of the next generation. While all women are not mothers or wives, this is still the primary role of women in life, though they are certainly not limited to only this role.

Mothers comfort and feed their children. They feed not only the physical child, but also the spiritual, mental and emotional child. This feeding nourishes and instructs, strengthens and invigorates, enlivens and comforts. Mothers provide this comfort and nourishment to their children and to society. Teaching naturally flows from this desire.

God describes Himself as a mother to Israel, “As one whom his mother comforteth, so will I comfort you; and ye shall be comforted in Jerusalem” (Is. 66:13). Paul said that they had brought the Gospel to the Thessalonians in a gentle manner, “as a nursing mother tenderly cares for her own children” (1 Thess. 2:7). This heart for their spiritual children caused Paul and those with him to gladly pour out their own lives for the Thessalonian believers. This is the heart God gives mothers for their children. Without this heart, nations are doomed.

There is a statue in Plymouth, Massachusetts, honoring the Pilgrim mother. On the base of that statue these words are engraved, “They brought up their families in sturdy virtue and a living faith in God without which nations perish.”

These qualities, imparted in the American home, are the foundation of our existence as a free nation. As the role of mothers is diminished in shaping the godly character of future generations, so will America decline. Mothers who fulfill their primary role will impact society in many ways.

Abigail Adams

Abigail Adams was one of the most inspirational and influential women in history. She was the first woman to be both the wife and mother of an American president, an honor she held solely until Barbara Bush, the wife of former President George H. W. Bush, saw her son George W. Bush sworn in as president.

It is said of Abigail that as a wife and inspiration to John Adams she “strengthened his courage, fired his nobler feelings and nerved his higher purposes. She was the source of his strength and the inspiration that gave him the power to rise above his own weaknesses as often as he did.”

An excerpt of a letter to her husband on the day he became president reveals much of her character:

You have this day to declare yourself head of a nation. “And now, O Lord, my God, thou hast made thy servant ruler over the people. Give unto him an understanding heart that he may know how to go out and come in before this great people, and that he may discern between good and bad. For who is able to judge this thy so great a people” were the words of a royal sovereign; and not less applicable to him who is invested with the chief magistracy of a nation, though he wear not a crown, nor the robes of royalty.

My thoughts and my meditations are with you, though personally absent; and my petitions to Heaven are that the things that make for peace may not be hidden from your eyes. My feelings are not those of pride or ostentation, upon the occasion. They are solemnized by a sense of the obligations, the important trusts, and numerous duties connected with it. That you may be enabled to discharge them with honor to yourself, with justice and impartiality to your country, and with satisfaction to this great people, shall be the daily prayer of your A.A.3

Abigail’s influence was not only instrumental to her husband’s achievements, but also those of her son, John Quincy Adams. She was responsible for his education — training that produced a great statesmen.

Abigail was John Quincy’s primary educator until age 10 or 11. As a 10-year-old, John Quincy knew French and Latin, read Rollins and Smollet, and helped manage the farm with his mother while his father was away serving the nation. At the same age he wrote to his father in a letter, “I wish, sir, you would give me some instructions with regard to my time, and advise me how to proportion my studies and my play, in writing, and I will keep them by me and endeavor to follow them.”4

At age 11, John Quincy traveled with his father to France, yet Abigail used her letters to continue the education she had so well begun at their home in Braintree, Massachusetts. In June of 1778 she wrote:

You are in possession of a naturally good understanding, and of spirits unbroken by adversity and untamed with care. Improve your understanding by acquiring useful knowledge and virtue, such as will render you an ornament to society, and honor to your country, and a blessing to your parents. Great learning and superior abilities, should you ever possess them, will be of little value and small estimation, unless virtue, honor, truth, and integrity are added to them. Adhere to those religious sentiments and principles which were early instilled into your mind, and remember, that you are accountable to your Maker for all your words and actions.5

In the same letter she encouraged John Quincy to pay attention to the development of his conduct by heeding the instruction of his parents; “for, dear as you are to me, I would much rather you should have found your grave in the ocean you have crossed . . . than see you an immoral, profligate, or graceless child.”

When he was 14 he received a U.S. Congressional diplomatic appointment as secretary to the ambassador of the court of Catherine the Great in Russia. Besides serving as president, he also served 18 years in the U.S. House of Representatives, was a U.S. Senator, was Secretary of State, and served as Foreign ambassador to England, France, Holland, Prussia and Russia. In addition to his scholarship and statesmanship, John Quincy had been trained in godly character and thought. He had a providential view of history6, as seen in his 1837 July 4th Oration7, where he spoke of America being a link in the progress of the Gospel throughout history, and where he recognized the founding of this nation upon Christian principles.

John Quincy once wrote of his mother:

My mother was an angel upon earth. She was a minister of blessings to all human beings within her sphere of action. . . . She has been to me more than a mother. She has been a spirit from above watching over me for good, and contributing by my mere consciousness of her existence to the comfort of my life. . . . There is not a virtue that can abide in the female heart but it was the ornament of hers.8

Sarah Edwards

Jonathan Edwards was perhaps the greatest theologian/philosopher in America’s history and was the leader in sparking the first Great Awakening in the 1730s. Much of his success was due to his wife, Sarah. She managed the household, was instrumental in raising their 11 children, and created an atmosphere of harmony, love and esteem in their home. Visitors frequently stayed overnight in the Edwards’ home and were more often affected by the character of the home than any words spoken by Jonathan in

conversation.

When George Whitefield visited them, he was deeply impressed with the Edwards’ children, with Jonathan and especially with Sarah — her ability to talk “feelingly and solidly of the things of God,” and her role of helpmate to her husband. Her example motivated him to marry the next year.9

A writer, who knew and visited the Edwards, Samuel Hopkins, wrote of Sarah’s training of her children:

She had an excellent way of governing her children. She knew how to make them regard and obey her cheerfully, without loud, angry words, much less heavy blows. . . . If any correction was necessary, she did not administer it in a passion. . . . In her directions in matters of importance, she would address herself to the reason of her children, that they might not only know her will, but at the same time be convinced of the reasonableness of it. . . . Her system of discipline was begun at a very early age and it was her rule to resist the first as well as every subsequent exhibition of temper or disobedience in the child . . . wisely reflecting that until a child will obey

his parents, he can never be brought to obey God.10

A study was done of 1,400 descendants of Jonathan and Sarah Edwards. There were 13 college presidents, 65 professors, 100 lawyers, 30 judges, 66 physicians, and 80 holders of public office including three senators, three governors, and a vice president of the United States. Sarah not only affected the lives of many during the time she lived, but through her descendants she has touched all of eternity.

Mercy Otis Warren

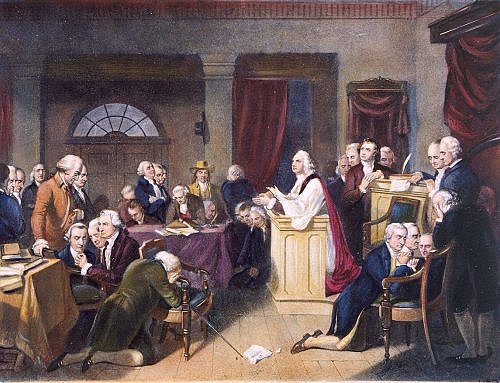

Many women carried their role as teachers beyond their families, for example Mercy Otis Warren. Mercy wrote one of the first histories of the American Revolution, History of the Rise, Progress and Termination of the American Revolution, which was quite unusual for a woman at that time.

She wrote this work with a desire to be of use to the newly formed American republic. She thought a principal responsibility of her writings was, “to form the minds, to fix the principles[,] to correct the errors, and to beckon by the soft allurements of love, as well as the stronger voice of reason, the young members of society (peculiarly my charge), to tread the path of true glory.”11 True history will inspire youth “to tread the path of true glory.”

In her writings, Mercy not only saw an opportunity to benefit her country, but to also fulfill her role as a mother—“to cultivate the sentiments of public and private virtue in whatever falls from her pen.”12 She agreed with the common sentiment of her day that history should train people, especially young people, in “public and private virtue.”13

Mama West

Benjamin West’s mother greatly influenced society through inspiring her son, the father of American painting. Raised in a plain Quaker home in Pennsylvania, Benjamin West (1738-1820) went on to become a very successful painter known throughout America and Europe. While serving as the president of the British Royal Academy, Benjamin gave much support to many of America’s first artists. He attributed his success to his mother.

When Benjamin West was seven years old, he was left one summer day with the charge of an infant niece. As it lay in the cradle and he was engaged in fanning away the flies, the motion of the fan pleased the child and caused it to smile. Attracted by the charms thus created, young West felt his instinctive passion aroused; and seeing paper, pen and some red and black ink on a table, he eagerly seized them and made his first attempt at portrait painting. Just as he had finished his maiden task his mother and sister entered. He tried to conceal what he had done, but his confusion arrested his mother’s attention, and she asked him what he had been doing. With reluctance and timidity, he handed her the paper, begging at the same time, that she would not be offended.14

His reluctance likely came from the strict Quaker tenets against graven images; and he wasn’t sure how his mom would respond. He had never seen a painting or portrait before.

Examining the drawing for a short time, she turned to her daughter and, with a smile, said, “I declare, he has made a likeness of Sally.” She gave him a fond kiss, which so encouraged him that he promised her some drawings of the flowers which she was then holding, if she wished to have them.

The next year a cousin sent him a box of colors and pencils, with large quantities of canvas prepared for the easel, and half a dozen engravings. Early in the morning after their reception, he took all his materials into the garret, and for several days forget all about school. His mother suspected that the box was the cause of his neglect of his books, and going into the garret and finding him busy at a picture, she was about to reprimand him; but her eye fell on some of his compositions, and her anger cooled at once. She was so pleased with them that she loaded him with kisses and promised to secure his father’s pardon for his neglect of school.

How much the world is indebted to Mrs. West for her early and constant encouragement of the immortal artist. He often used to say, after his reputation was established, “My mother’s kiss made me a painter.”15

Building Nations Through the Home

Besides the primary source of education, homes are also the seed-beds of the Gospel, civil liberty, civility, health and welfare. They, not the government, are to be the primary provider of health, education, and welfare. Homes are the foundation of society. It is here that women have great influence.

The Gospel is spread primarily through the homes of a nation. After Lydia was converted by Paul (his first convert in Europe), she introduced her household to God and then opened her home to Paul, and hence, to the Gospel (Acts 16:14-15). Christianity first spread into Europe through her home. Women, more than anyone, can make the atmosphere of their home conducive to spreading the Gospel.

Civil liberty is also chiefly spread through homes. Motherhood is critical for the development of the character and self-government necessary to support a free nation. Mother, and educator of women in the 19th century, Lydia Sigourney, said:

For the strength of a nation, especially of a republican nation, is in the intelligent and well-ordered homes of the people. And in proportion as the discipline of families is relaxed, will the happy organization of communities be affected, and national character become vagrant, turbulent, or ripe for revolution.16

Further, homes provide the foundation of happiness and comfort in a society. It is in homes that morals and true knowledge are imparted. It is there that spiritual and mental health is cultivated, which provide the most important ingredient for physical health. Caring for the elderly, the sick, the orphaned and the needy should also be in the home. Daniel Webster wrote:

[H]appiness . . . depends on the right administration of government, and a proper tone of public morals. That is a subject on which the moral perceptions of woman are both quicker and juster than those of the other sex. . . . It is by the promulgation of sound morals in the community, and more especially by the training and instruction of the young, that woman performs her part towards the preservation of a free government. It is generally admitted that public liberty, and the perpetuity of a free constitution, rest on the virtue and intelligence of the community which enjoys it. How is that virtue to be inspired, and how is that intelligence to be communicated?. . . . Mothers are, indeed, the affectionate and effective teachers of the human race.17

Dolley Madison

As the first lady, Dolley Madison was the facilitator of the nation’s business. Because President Thomas Jefferson’s wife had died at a young age and he never remarried, Dolley served as White House hostess during his administration.

She continued this role when her husband, James, succeeded Jefferson as president. For 16 years she set a home atmosphere for the White House and the office of the presidency. She was the first to serve state dinners at the White House, where much of the nation’s business was, and has been, accomplished. And during the War of 1812 she risked great danger by staying in the White House to save important paintings and documents when the British troops were marching into Washington.

Narcissa Whitman

Narcissa and Marcus Whitman were among the first missionaries and pioneers to the Oregon territory. Narcissa and another missionary’s wife were the first two American women to travel over the Rockies. The settlement of the northwest took place through the Whitman home. Narcissa was known for her faith, courage and determination. In the end those she came to serve took Narcissa’s life. Indians martyred her and her husband.

Harriet Beecher Stowe

When Harriet Beecher Stowe visited President Abraham Lincoln in the White House he first greeted her with the words, “So this is the little lady who made this big war.”18 He made this statement due to the influence of her book, Uncle Tom’s Cabin. A runaway best seller in the 1850s, it sold more than 100,000 copies in six months and put her on the forefront of America’s abolition movement. She was acclaimed by literary and political leaders throughout the world, from Charles Dickens to Mark Twain to England’s Queen Victoria.

Prior to writing the book, Harriet didn’t have much time to do anything outside the home, “I am but a mere drudge with few ideas beyond babies and house-keeping.” When her husband Calvin’s salary was cut in half at the seminary where he worked, Harriet’s writing developed out of necessity.

Calvin had always encouraged her in her writing, believing it was part of God’s fate for her. He told her to let her writing flow, for as a result her husband and children would call her blessed, like the woman in Proverbs 31 who uses her talents for good.

She began to write some articles and submit them to eastern magazine publishers. Her success was immediate, though she continued to face many personal challenges. With her rapidly growing family, eventually numbering seven children, came an increase in physical sickness, plus all the pressures she faced caused her to feel emotionally drained. After she heard that her brother had been found shot to death outside his home, she broke down physically and emotionally. During a time of recuperation, she began writing a series for a magazine that became Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Concerning Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Harriet said she did not write it, “I was only the instrument. The Lord wrote the book.”19

Though this book led to international fame and visits with many famous people, Harriet remained faithful to her duties as a wife and mother. She also assumed leadership in the anti-slavery movement. With the help of her husband and brother, she drew up an anti-slavery petition, got 3,000 ministers to sign it, and presented it to the U.S. Congress.

Harriet Beecher Stowe had as much to do with the freeing of the slaves in America as anyone. And she brought about this great social change while fulfilling her duties and responsibilities in the home.

Persevering Through Adversity

Many women have contributed to the advancement of God’s purposes with great circumstances to overcome.

Pamela Cunningham

Pamela Cunningham had become an invalid when she fell from a horse as a girl. When her mother visited Mount Vernon in 1853 and reported to Pamela the state of disrepair to which first President George Washington’s home had fallen (she had seen its stateliness as a child), Pamela began “to emerge from her sheltered life and participate openly in public affairs.” She took it upon herself to preserve the memory of “the Father of our Country.”

Elswyth Thane writes in Mount Vernon is Ours:

The Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association is not sponsored by nor beholden to the Federal Government or the State of Virginia. It stands alone, its original charter having been granted in 1858, when ladies were not supposed to be capable of conducting anything like public affairs, and it was the creation of one resolute woman who at the age of 37 acquired what even her friends at first considered an impracticable obsession. She had made up her mind that the home, which George Washington loved, should not be allowed to fall down in ruins from neglect. Not the uncooperative Washington family, the skeptical Virginia Legislature, nor her own condition of chronic invalidism could daunt her, nor swerve her from her apparently impossible purpose. As an example of sheer grit and courage, laced with Southern charm, Ann Pamela Cunningham remains unique.20

God’s providence was evident in all she did to accomplish the task. She enlisted the assistance of Edward Everett (pastor, member of congress, Governor of Massachusetts, senator, President of Harvard, minister to Great Britain, and known for his oratory), raised the money, persuaed John Augustine Washington to sell the land, and obtained the approval of the state of Virginia. In her invalid condition all the travel and work nearly killed her, but she persevered, and her vision was accomplished. The organization which she started, The Mount Vernon Ladies Association, is the oldest non-government sponsored organization for the preservation of an historic site.

Phillis Wheatley

Phillis Wheatley was the first significant black writer in America, and her book of poems was probably the first book published by a black American. Her accomplishments are even more admirable when considering her circumstances in life.

Phillis came as a slave to America from Africa in 1761, at about the age of eight. When she arrived she knew no English and was frail. While she quickly learned English, and much more, she remained frail all her life. John and Susanna Wheatley purchased Phillis and incorporated her into their family life. Susanna and her daughter, Mary, tutored her in the Bible, English, Latin, history, geography and Christian principles. Phillis learned quickly and acquired a better education than most women in Boston had at the time.

Phillis began writing poetry at age 12 and many of her poems reflect her strong Christian faith. At the age of 18, Phillis joined the Old South Congregational Church. She was not only glad to be a Christian but was also proud to be an American. God was her first priority, followed by herself and the Wheatley family.

Shortly after her first book of poems was published in 1773, John Wheatley gave Phillis her freedom. In her short life she gained much renown and met many famous people, including President George Washington, about whom she had written a poem.

The following poem reveals Phillis Wheatley’s providential view of life, recognizing God’s hand in her own circumstances and history.

On Being Brought From Africa to America

‘TWAS mercy brought me from my Pagan land, Taught my benighted soul to understand That there’s a God, that there’s a Saviour too: Once I redemption neither sought nor knew. Some view our sable race with scornful eye, “Their colour is a diabolic die.” Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain, May be refin’d, and join the angelic train.21

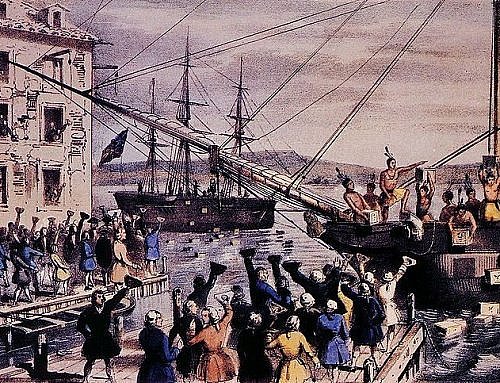

A Lady of Philadelphia

The following is from The Women of the American Revolution by Elizabeth F. Ellet:

A letter found among some papers belonging to a lady of Philadelphia, addressed to a British officer in Boston, and written before the Declaration of Independence, reads, in part,

“I will tell you what I have done. My only brother I have sent to the camp with my prayers and blessings. I hope he will not disgrace me; I am confident he will behave with honor, and emulate the great examples he has before him; and had I twenty sons and brothers they should go. I have retrenched every superfluous expense in my table and family; tea I have not drunk since last Christmas, nor bought a new cap or gown since your defeat at Lexington; and what I never did before, have learned to knit, and am now making stockings of American wool for my servants; and this way do I throw in my mite to the public good. I know this — that as free I can die but once; but as a slave I shall not be worthy of life. I have the pleasure to assure you that these are the sentiments of all my sister Americans. They have sacrificed assemblies, parties of pleasure, tea drinking and finery, to that great spirit of patriotism that actuates all degrees of people throughout this extensive continent. If these are the sentiments of females, what must glow in the breasts of our husbands, brothers, and sons! They are as with one heart determined to die or be free. It is not a quibble in politics, a science which few understand, that we are contending for; it is this plain truth, which the most ignorant peasant knows, and is clear to the weakest capacity — that no man has a right to take their money without their consent. You say you are no politician. Oh, sir, it requires no Machiavelian head to discover this tyranny and oppression. It is written with a sunbeam. Every one will see and know it, because it will make every one feel; and we shall be unworthy of the blessings of Heaven if we ever submit to it. . . . Heaven seems to smile on us; for in the memory of man, never were known such quantities of flax, and sheep without

number. We are making powder fast, and do not want for ammunition.”22

A Good Lady and Her Two Sons

The following story is from Annals of the American Revolution by Jedidiah Morse.

The female part of our citizens contributed their full proportion in every period, towards the accomplishment of the revolution. They wrought in their own way, and with great effect. An anecdote which we have just seen in one of our newspapers, will explain what I mean.

A good lady — we knew her when she had grown old — in 1775, lived on the sea-board, about a day’s march from Boston, where the British army then was. By some unaccountable accident, a rumour was spread, in town and country, in and about there, that the Regulars were on a full march for the place, and would probably arrive in three hours at farthest. This was after the battle of Lexington, and all, as might be well supposed, was in sad confusion — some were boiling with rage and full of fight, some with fear and confusion, some hiding their treasures, and others flying for life. In this wild moment, when most people, in some way or other, were frightened from their property, our heroine, who had two sons, one about nineteen years of age, and the other about sixteen, was seen by our informant, preparing them to discharge their duty.

This lady had a vision for the cause of liberty and had imparted this to her sons as well. Now, as the cause entered a phase where a greater commitment was required, she was ready to send them to the battle.

The eldest she was able to equip in fine style — she took her husband’s fowling-piece, “made for duck or plover,” (the good man being absent on a coasting voyage to Virginia) and with it the powder horn and shot bag; but the lad thinking the duck and goose shot not quite the size to kill regulars, his mother took a chisel, cut up her pewter spoons, and hammered them into slugs, and put them into his bag, and he set off in great earnest, but thought he would call one moment and see the parson, who said well done, my brave boy — God preserve you — and on he went in the way of his duty. The youngest was importunate for his equipments, but his mother could find nothing to arm him with but an old rusty sword; the boy seemed rather unwilling to risk himself with this alone, but lingered in the street, in a state of hesitation, when his mother thus upbraided him. “You John H*****, what will your father say if he hears that a child of his is afraid to meet the British, go along; beg or borrow a gun, or you will find one, child — some coward, I dare say, will be running away, then take his gun and march forward, and if you come back and I hear you have not behaved like a man, I shall carry the blush of shame on my face to the grave.” She then shut the door, wiped the tear from her eye, and waited the issue; the boy joined the march. Such a woman could not have cowards for her sons.

Instances of refined and delicate pride and affection occurred, at that period, every day, in different places, and in fact this disposition and feeling was then so common, that it now operates as one great cause of our not having more facts of this kind recorded. What few there are remembered should not be lost. Nothing great or glorious was ever achieved which woman did not act in, advise, or consent to.23

Making Your Life Count

“Dear God, guide me. Make my life count.” A love of God, an understanding of His purpose, a love of learning, a heart to nourish and teach and a burning desire to fulfill God’s plan — these are the characteristics you should cultivate to make your life count.

We can see these qualities in Susannah Wesley, Sarah Edwards, Abigail Adams and others. If God has put a desire in your heart, no matter what the nature, don’t let it die out, but seek to fan the flames and be responsible to fulfill your duties where God has you.

Katherine Lee Bates

Katherine Lee Bates was a woman who had a burning desire to leave a permanent legacy. She wrote poems and stories from the time she was a young girl. She stated, “If I could only write a poem people would remember after I was dead, I would consider my life had been worth living. That’s my dream, to write something worthwhile, something that will live after me.”

All through college and her rise as a teacher, then full professor and head of the English Department of a college for women, her life’s dream was always burning in her heart. It burned for over two decades. When she was 34 years old Katherine Lee Bates did write those words that would live after her. It was atop Pike’s Peak looking out over the mountains, fields, and sky that she felt love for her country such as she had never had before and the words came to her:

O beautiful for spacious skies

For amber waves of grain

For purple mountain majesties

Above the fruited plain!

America, America!

God shed His grace on thee,

And crown thy good with brotherhood

From sea to shining sea.

To Godly women in America: the role you play in advancing liberty, nations, and God’s Kingdom may be one of renown, as a Harriet Beecher Stowe, or it may be one of support, as a Sarah Edwards, or it may be one where your children become great leaders, as with Susanna Wesley or Abigail Adams, or it may be one where you fulfill God’s plan by overcoming adversity, as Pamela Cunningham. It is most likely that history will never take notice of the role you play, but the impact you have is immeasurable, for you are the shapers of the generations to come, you are the preservers of the happiness and freedom of our nation, you are the creators of a new generation. Without you our nation will surely perish, but with you we can have the greatest hopes for the future fortunes of our country and the advancement of God’s truth and liberty throughout the nations.

Most of the problems society faces today have their solution in the homes, for here is where a new generation is being formed. We need a generation of great men and women and children who will not be the “creatures” of our age, but the “creators” of it.

Women — as those that form the character of the next generation, as transmitters and preservers of liberty, as teachers of the human race, as co-managers of the homes, as providers of education, health, and welfare — will play a central role in creating a new age, one where God is glorified and His liberty extends to all.

End Notes

- The Christian History of the American Revolution,

Consider and Ponder, Verna M. Hall, compiler, San Francisco: Foundation for

American Christian Education, 1976, p. 74. - Daniel Webster, “Remarks to the Ladies of Richmond,

October 5, 1840,” The Works of Daniel Webster, Boston: Little, Brown, &

Co., 1854, 2:107-108. - Nobel Deeds of American Women, J. Clement, editor,

Boston: Lee & Shepherd, 1851, pp. 48-49. - Hall, p. 605.

- Hall, p. 607, quoting from Life, Administration and Times

of John Quincy Adams by John Robert Irelan, 1887, pp. 20-22. - Adams read through Rollins Ancient History when he was

10. His mother began reading it to him a few years before. See Hall, p. 605 for

Rollins view of history. - John Quincy Adams, “An Oration Delivered before the

Inhabitants of the Town of Newburyport

at their Request on the Sixty-First Anniversary of the Declaration of

Independence, July 4, 1837” (Newburyport: Charles Whipple, 1837). - John T. Faris, Historic Shrines of America, New York:

George H. Doran Co., 1918, p. 49. - William J. Petersen, Martin Luther Had a Wife, Wheaton,

Ill.: House Publishers, p. 87. - Ibid., p. 82-83.

- Mrs. Mercy Otis Warren, History of the Rise Progress and

Termination of the American Revolution, Indianapolis: reprinted by Liberty

Classics, 1988, p. xvii. - Ibid.

- Ibid., p. xxi.

- Noble Deeds of American Women, pp. 202-203.

- Ibid.

- Lydia H. Sigourney, Letters to Young Ladies (1852), quoted

in Christian History of the Constitution of the United States of America,

compiled by Verna M. Hall, San Francisco: Foundation for American Christian

Education, 1980, p. 410. - “Remarks to the Ladies of Richmond, October 5, 1840,”

The Works of Daniel Webster, 2:105-108. - William J. Petersen, Harriet Beecher Stowe Had a

Husband, Wheaton, Ill.: Tyndale House Publishers, 1983, p. 134. - Ibid., p. 131.

- Elswyth Thane, Mount Vernon Is Ours, The Story of Its

Preservation, New York: Duell, Sloan, and Pearce, 1966, p. 3. - The Poems of Phillis Wheatley, Julian D. Mason, Jr.,

editor, Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1989 , p. 53. - The Women of the American Revolution, by Elizabeth F.

Ellet, 1849, in Hall, Consider and Ponder, p. 74. - Jedidiah Morse, Annals of the American Revolution, Port

Washington, NY: Kennikat Press, 1968. Reprint of original, first published in

1824, p. 233.