Stephen McDowell

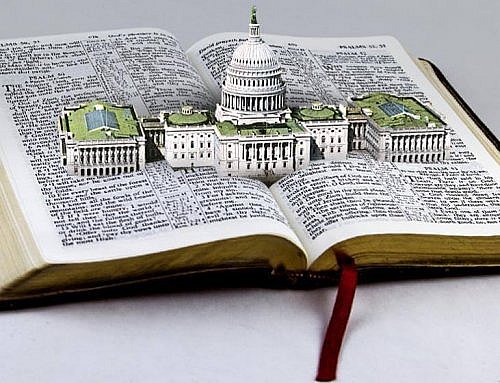

Several years ago, a bill was introduced in Congress recommending—not requiring—Americans to observe a national day of prayer and fasting in response to various violent acts in America. It was voted on under special rules for non-controversial bills and thus needed a two-thirds majority to pass. It fell two votes short, 275 to 140. One opponent, Rep. Chet Edwards (D–Texas), harshly attacked the bill as unconstitutional and morally wrong. He said that Congress has no business telling Americans when to pray.

While Rep. Edwards claimed this was unconstitutional, he certainly did not obtain this view from the Founders for they were continually declaring days of prayer. From the landing of the Jamestown settlers at Cape Henry in 1607 to the Pilgrims at Plymouth and the New England Puritans through the establishment of Georgia as the thirteenth colony, governments at all levels proclaimed numerous Days of Prayer and Fasting and Thanksgiving.

One example of this occurred in October 1746 when France sent a fleet to attack Boston. Governor Shirley proclaimed a Fast Day and people everywhere thronged to the churches to pray for deliverance. God miraculously answered their prayers by sending a storm and pestilence to wipe out the French fleet. Everyone gave thanks to God.[i]

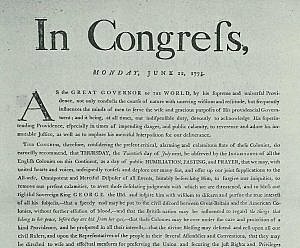

This not only occurred before independence, but throughout the Revolution and up to the present. During the Revolutionary War the Continental Congress issued at least six different prayer and fast day proclamations and seven different thanksgiving proclamations. These were issued after events such as the surrender of British General Burgoyne at Saratoga, the discovery of the treason of Benedict Arnold, and the surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown. In the proclamation from the fall of 1777, they recommended for everyone to confess their sins and humbly ask God, “through the merits of Jesus Christ, mercifully to forgive and blot them out of remembrance” and thus He would be able to pour out His blessings upon every aspect of the nation.[ii]

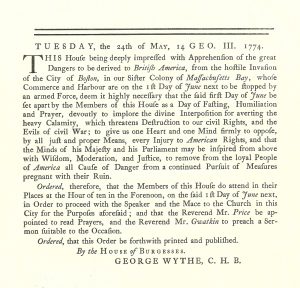

The individual states proclaimed numerous such days as well. The Virginia House of Burgesses set apart June 1, 1774, as a day of fasting and prayer in response to England closing the port of Boston. On the day British troops fired upon the minutemen at Lexington (April 19, 1775) the colony of Connecticut was observing a “Day of publick Fasting and Prayer” as proclaimed by Governor Trumbull a month before. In March 1776 Massachusetts set aside “Friday, the 17th day of May … as a day of humiliation, fasting, and prayer; that we may, with united hearts, confess and bewail our manifold sins and transgressions, and, by a sincere repentance and amendment of life, appease his righteous displeasure, and through the merits and mediation of Jesus Christ obtain his pardon and forgiveness.” New York set aside August 27, 1776, “as a day of Fasting, Humiliation, and Prayer to Almighty God, for the imploring of His Divine assistance in the organization and establishment of a form of Government for the security and perpetuation of the Civil and Religious Rights and Liberties of Mankind.”[iii]

Many Americans today believe that our Founders established a separation of church and state in our founding documents, and hence, God can have nothing to do with public life. They declare government endorsed prayer is unconstitutional, and they often look to Thomas Jefferson to justify their belief. But Jefferson was no strict separationist, as many of his public actions reveal. He penned the resolve for Virginia’s day of fasting and prayer on June 1, 1774.[iv] While Governor in 1779, he issued a proclamation “appointing Thursday the 9th day of December next, a day of publick and solemn thanksgiving and prayer to Almighty God, earnestly recommending to all the good people of this commonwealth, to set apart the said day for those purposes.”[v]

If in session, Congress and the state assemblies would even go to church together as a body to observe these days. In 1787 a committee of representatives of all the states, gratefully looking back over all the preceding years, set apart October 19, 1787, “as a day of public prayer and thanksgiving” to their “all-bountiful Creator” who had conducted them “through the perils and dangers of the war” and established them as a free nation, and gave “them a name and a place among the princes and nations of the earth.”[vi]

The first President, George Washington, issued days of thanksgiving and days of prayer as recommended by Congress. Most Presidents up until today have followed this example, with about 200 such proclamations being issued by national government leaders.[vii] The 140 congressmen who voted against the bill appointing a day of prayer and fasting were separating themselves from the precedent of American history. Public, as well as private, prayer has been an integral part of our history.

[i] Catherine Drinker Bowen, John Adams and the American Revolution, New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1950, p. 10-12.

[ii] B.F. Morris, Christian Life and Character of the Civil Institutions of the United States, Philadelphia: George W. Childs, pp. 530-531.

[iii] See Beliles and McDowell, America’s Providential History, p. 141. Peter Force, American Archives: A Documentary History of the English Colonies in North America, Fourth Series, Washington: M. St. Clair and Peter Force, 1848, pp. 310, 1470. W. DeLoss Love, The Fast and Thanksgiving Days of New England, New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1895, pp. 502-506. B.F. Morris, Chapters 22-23.

[iv] Resolution Virginia House of Burgesses, Tuesday, the 24th of May, 14 GEO. III. 1774, facsimile printing by Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

[v] The Virginia Gazette, Nov. 20, 1779, Number 4, Williamsburg: Printed by Dixon & Nicolson.

[vi] See B. F. Morris, and W. DeLoss Love, The Fast and Thanksgiving Days of New England. Love lists over 1300 Days of Prayer and Fasting, and Prayer and Thanksgiving declared by governments at all levels from 1620 – 1813.

[vii] See A Compilation of the Messages of the Presidents, James D. Richardson, ed., New York: Bureau of National Literature, 1897.