For PDF Version: Fast and Thanksgiving Days of New England

America’s tradition of celebrating days of thanksgiving dates from our earliest history. The first Americans were predominantly Christians who embraced the doctrine of Divine Providence, seeing God in history as “directly supervising the affairs of men, sending evil upon the city . . . for their sins, . . . or blessing his people when they turn from their evil ways” (Love, 41). Looking to the Scriptures for the source of their law, both personal and civil, they firmly believed God’s bless ings would come upon those who obey His commands and curses would come upon the disobedient (see Deuteronomy 28 and Leviticus 26). This is why during times of calamity or crisis both church and civil authorities would proclaim days of fasting and prayer; and when God responded with deliverance and blessing, they would proclaim days of thanksgiving and prayer. Such days of appeal to God were not rare, but a regular part of life in early America.

ings would come upon those who obey His commands and curses would come upon the disobedient (see Deuteronomy 28 and Leviticus 26). This is why during times of calamity or crisis both church and civil authorities would proclaim days of fasting and prayer; and when God responded with deliverance and blessing, they would proclaim days of thanksgiving and prayer. Such days of appeal to God were not rare, but a regular part of life in early America.

In his thoroughly researched book, The Fast and Thanksgiving Days of New England, W. DeLoss Love, Jr. lists thousands of these days that were proclaimed by governments and churches in New England from 1620 until 1815 (with the practice continuing to his time, 1894, and beyond). Love records the history of how these days originated and gives many specific examples of events, historical and natural, that precipitated official proclamations (two of these are included below, and more in chapter 8 of America’s Providential History, A Documentary Sourcebook). The number of proclamations for public days of fasting or thanksgiving by governments at all levels (local, state, and national, with most issued on the state level) include: over 1000 from 1620–1776; about 60 from 1776–1788; and over 225 from 1789–1815.

During observance of fast and thanksgiving days, people would gather at their local meeting houses and churches to hear a sermon. Many of these sermons were printed and distributed for study. Love’s bibliography includes 622 fast and thanksgiving day sermons that were published, dating from 1636 to 1815.

Love’s book, and the following excerpts from it, clearly reveal that those who settled and founded America were Christian. In times of need they cried out to God and He heard them and answered their prayers. Time and time again He brought about a “divine deliverance” in order to fulfill His purposes in America and in history.

The following excerpts are from: W. DeLoss Love, Jr., The Fast and Thanksgiving Days of New England, New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Co., 1895.

Drought of 1633

The spring of 1632 came. It was cold and wet. Corn planted in the lowlands, which were cleared and could be easier cultivated, was an utter failure. Some fields that would otherwise have yielded well were destroyed by worms, and, while those who had tilled the sandy soil did better that year, the harvest was very inadequate. Again they were dependent, to a large extent, upon the products of the sea; but it was not so easy to obtain them, for the winter of 1632–3 was very severe. The Charles River was frozen over, and successive snow-storms piled the drifts high round about. They were only delivered by the coming of a ship in March from Virginia, laden with corn. In the spring their struggles were renewed. They had hopes that their third planting, of greater extent than the two years previous, would release them from the tyranny of want. But erelong a new enemy was discovered, — the drought, which they learned in subsequent years to dread. They assembled in their churches, though at what times we know not, and besought the Lord for his mercy. Doubtless the season was well advanced, and their corn was withering in its earing time. Johnson says: “Thus it befell, the extreame parching heate of the sun . . . began to scorch the Herbs and Fruits, which was the chiefest meanes of their lively-hood.” The same writer emphasizes the urgency of their prayers. They could not refrain from tears in their religious assemblies as they importuned God for rain. The answer came, and the story is a repetition of that recorded of Plymouth ten years before. In the quaint phraseology of this author: “As they powred out water before the Lord so at that very instant the Lord showred down water on their Gardens and Fields, which with great industry they had planted, and now had not the Lord caused it to raine speedily their hope of food had beene lost.” Wherefore they celebrated his goodness in a thanksgiving October 16, the first public thanksgiving of the Bay Colony in which the gathering of the harvest bore a conspicuous part. Thus, be it noted, the two colonies of Massachusetts, in their early experiences, had the same reason to recognize God as the giver of harvests, and thus in hunger, like Ruth and Naomi, they were pledged to Him and to one another. [pp. 107-108]

Defeat of French Fleet, 1746

In the month of September [1746] rumors were abroad of a French fleet hovering off the coast, designed against Boston. It was soon ascertained that ships had been seen to the eastward, and a veritable armada, under the Duke d’Anville, was expected at any time. The New England metropolis was in consternation. Troops were hastily mustered for defense. A public fast was set for October 16, and their fears were wrought into its services. Doubtless they would have been realized, too, to the fullest extent, had it not been for a tempest similar to that which had destroyed the Spanish Armada. Who will say that this was not truly a divine deliverance? So Thomas Prince thought, and on the thanksgiving November 27, 1746, he had an opportunity to detail it, as he did in his printed sermon, “The Salvations of God in 1746.” That fleet he sets forth as the object of divine vengeance. The facts were, that it suffered delays, a fever wasted the troops until thousands were buried in the deep, the treacherous shoals engulfed them, their commander died of poison, his successor fell on his sword, the rumor of an English fleet frightened them, and at last a furious storm of wind, rain, and hail arose and scattered them as the chaff. The preacher makes much of the remarkable coincidence that it was on the day of their fast that the glorious God “put a total end to their mischievous enterprise.” “Thus when on our solemn Day of General Prayer we expressly cried to the Lord, ‘Let God arise, let his enemies be scattered, . . .’ then his own Arm brought Salvation to us and his Fury upheld him. He trode down our Enemies in his Anger, he made them drunk in his Fury, and he brought down their Strength to the Earth. Terrors took hold on them as Waters: A Tempest bore them away in the Night: The East Wind carried them away, and they departed; and with a Storm he hurled them out of their Place.” [pp. 305-306]

(You can order a copy of America’s Providential History, A Documentary Sourcebook on our online store.)

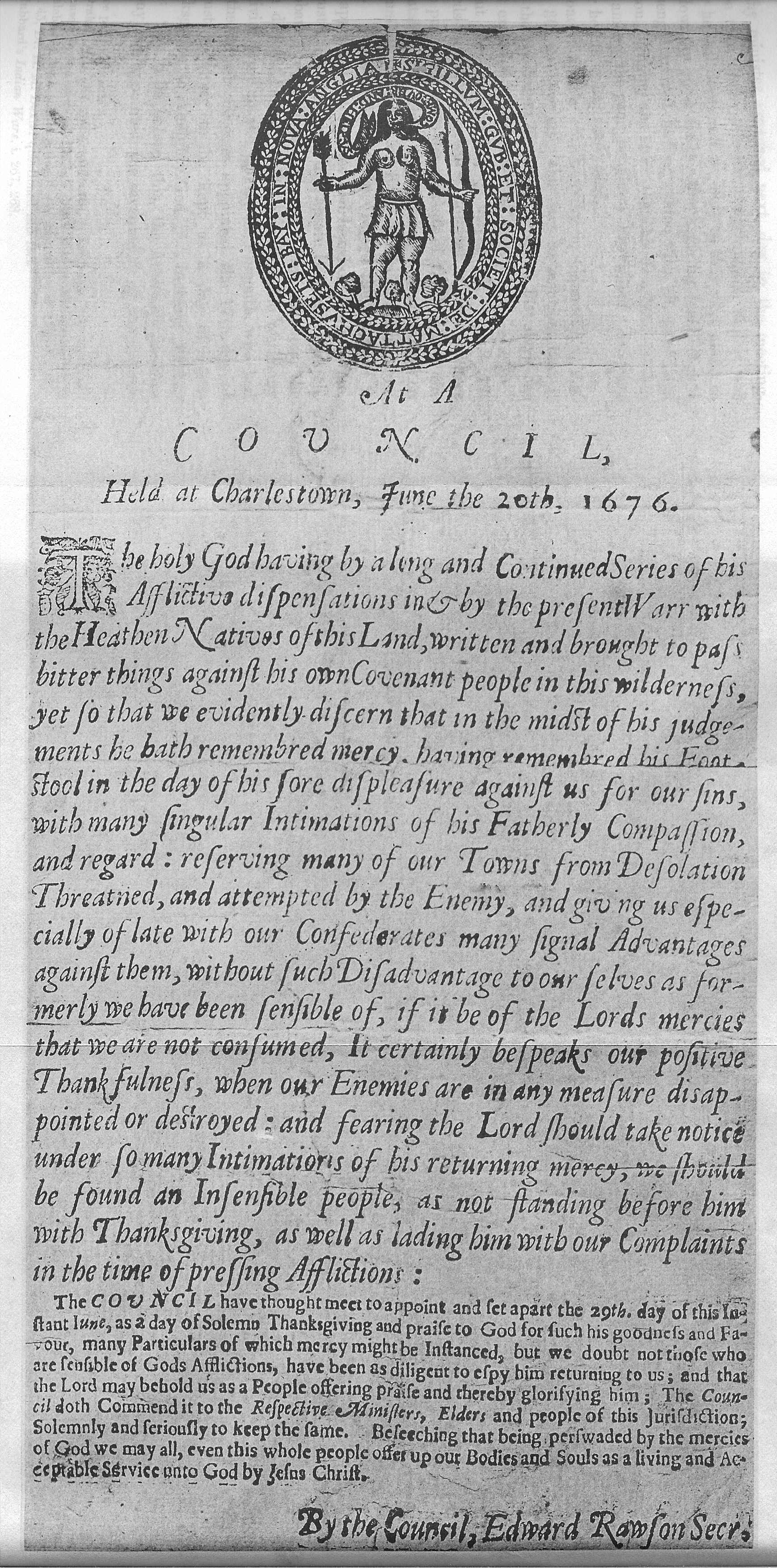

On June 20, 1676, the Council of Massachusetts appointed June 29 as a Day of Thanksgiving and Prayer, in response to the colonists’ victory in King Philip’s War. The printed broadside of this proclamation is the earliest thanksgiving broadside known.

On June 20, 1676, the Council of Massachusetts appointed June 29 as a Day of Thanksgiving and Prayer, in response to the colonists’ victory in King Philip’s War. The printed broadside of this proclamation is the earliest thanksgiving broadside known.

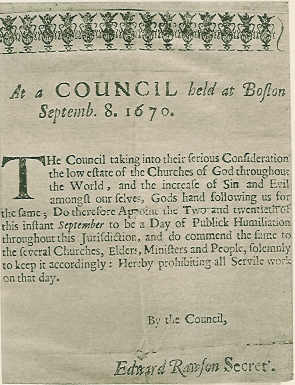

Possibly the first printed broadside for a Day of Prayer, September 8, 1670. Before this the numerous proclamations were written by hand.

Possibly the first printed broadside for a Day of Prayer, September 8, 1670. Before this the numerous proclamations were written by hand.