Providence Foundation

P.O. Box 6759

Charlottesville, VA 22906

To place order:

434-978-4535

America Relies Upon God Public Days of Fasting and Thanksgiving during the American Revolution

By Stephen McDowell

As America has humbled herself before God and been obedient to His commandments, He has poured out His blessings upon this nation in innumerable ways. It was by God’s hand and for

His purposes that America came into being as the world’s first Christian republic, but it was through the people who covenanted themselves with God that He was able to do His work.

Almost all the people who colonized America, though they were from different denominations and Christian persuasions, embraced the Puritan doctrine of Divine Providence, seeing God in history as “directly supervising the affairs of men, sending evil upon the city . . . for their sins, . . . or blessing his people when they turn from their evil ways.”1 Looking to the Scriptures for the source of their law, both personal and civil, they firmly believed God’s blessings would come upon those who obey His commands and curses would come upon the disobedient (see Deuteronomy 28 and Leviticus 26).

Divine Providence, seeing God in history as “directly supervising the affairs of men, sending evil upon the city . . . for their sins, . . . or blessing his people when they turn from their evil ways.”1 Looking to the Scriptures for the source of their law, both personal and civil, they firmly believed God’s blessings would come upon those who obey His commands and curses would come upon the disobedient (see Deuteronomy 28 and Leviticus 26).

This is why during times of calamity or crisis both church and civil authorities would proclaim days of fasting and prayer; and when God responded with deliverance and blessing, they would proclaim days of thanksgiving and prayer. From 1620 until the American Revolution at least 1000 such days were proclaimed by governments at all levels, and many more by various churches.2 This continued during our struggle for independence, through our first century as a nation, and, in some measure, even up until today.

Beginning in the late 1730s and continuing for about two decades, a great awakening occurred in America. This revival of Christianity set on fire the hearts of the people all over the colonies,

which in turn produced a greater morality and godliness than before existed in this nation. This was quite phenomenal for virtue had always permeated America. One example of this is attested to by historian James Truslow Adams, who said, “I have found only one case of a colonial traveler being robbed in the whole century preceding the Revolution.”3

The Great Awakening had such an impact upon the colonies that in some towns almost the entire populace was converted to Christ.

Benjamin Franklin wrote of this time period that “it seemed as if all the world were growing religious, so one could not walk thro’ the town in an evening without hearing psalms sung in different families of every street.”4

This revival of Christianity in the hearts of the people had “expression not merely in church attendance, but in all the activities of life.”5 Universities such as Princeton, Rutgers, Dartmouth and Brown were founded in order to supply all the colonies with learned and influential clergy. These universities produced not only Godly clergy but Godly leaders in civil government, business, and every other aspect of life.

Providentially, this awakening occurred while our future Founding Fathers were young men. The men who won the Revolutionary War, formed our Constitutional Republic, and set our

nation properly on course were thus equipped with the virtue, morality, self-government, and Biblical worldview necessary for their future stations. Even the non-Christians, as Franklin and

Jefferson, were affected in this way.

Franklin said he, “never doubted . . . the existence of the Deity; that He made the world, and governed it by His Providence;. . . that all crime will be punished, and virtue rewarded, either here or hereafter.”6

The ideas upon which our nation was birthed — the right of man to life, liberty, and property— had their origin in God. As they originated in God, they were also secured due to His blessings upon this nation. He blessed not only individuals, but the entire nation. As America humbled herself before God by obedience to His Word and acknowledgment of her dependence upon Him for success in the Revolutionary War and the formation of the new nation, God not only provided wise and virtuous leaders, but also supernaturally intervened on behalf of the American army on many occasions.

From the initial conflict with Britain, the American Colonies relied upon God. George Washington’s words to his wife upon departure to take command of the Continental army, reflected the heart of the American people: “I shall rely . . . confidently on that Providence, which has heretofore preserved and been bountiful to me.”7 To punish Massachusetts for its action at the Boston Tea Party, England closed the Boston port on June 1, 1774. The response of the colonies revealed in Whom they looked for help. The Virginia House of Burgesses, in resolves penned by Jefferson, “set apart the first day of June as a day of fasting and prayer, to invoke the divine interposition to give to the American people one heart and one mind to oppose by all just means every injury to American rights.”8 On that day large congregations filled the churches. This occurred not only in Virginia but throughout the colonies.

Action followed this prayer as the colonists began to voluntarily provide aid and encouragement to Boston as that city’s commerce was cut off by the British blockade. This voluntary and universal action revealed that “beneath the diversity that characterized the colonies, there was American unity.”9 The American people recognized this unity came from a common Christian bond among the people of all the colonies. In response to the charity that flowed into the city, the Boston Gazette of July 11, 1774, responded by writing, “my persecuted brethren of this metropolis, you may rest assured that the guardian God of New England, who holds the hearts of his people in his hands, has influenced your distant brethren to this benevolence.”10 A few months later, in September of 1774, the first Continental Congress assembled in Philadelphia. The first act of the first session of the Congress was to pass a resolution calling for the opening of Congress the next day with prayer by Rev. Duché. The next morning Rev. Duché did pray and read from the thirty-fifth Psalm, as Washington, Henry, Lee, Jay and others knelt and joined with him in prayer.

John Adams wrote about this scene in a letter to his wife: “I never saw a greater Effect upon an audience. It seemed as if Heaven had ordained that Psalm to be read on that Morning. . .. It has had an excellent Effect upon every Body here.”11

God’s involvement in the founding of America is again seen on April 19, 1775. This day marked the battle of Lexington, of which Rev. Jonas Clark proclaimed: “From this day will be dated the liberty of the world.”12 It was his parishioners who shed the first blood of the Revolution, and it was on his church lawn that it occurred. God made certain that on this day His people had proper support, for on April 19, the entire colony of Connecticut was fasting and praying. On March 22, when the Governor of Connecticut, Jonathan Trumbull, proclaimed April 19 as a “Day of publick Fasting and Prayer,” he probably did not realize the significance of that date; but the One who rules heaven and earth and directs the course of history undoubtably knew and was able to direct the humble hearts of the colonists to pray.

In part, Trumbull’s proclamation asked,

“that God would graciously pour out His Holy Spirit on us, to bring us to a thorough Repentance and effectual Reformation, that our Iniquities may not be our Ruin; that He would restore, preserve and secure the Liberties of this, and all the other British American Colonies, and make this Land a mountain of Holiness and habitation of Righteousness forever.”13

Connecticut was not the only colony to lay the foundations of the War for Independence in prayer, for on April 15, 1775, Massachusetts officially proclaimed May 11 to be set apart as a “Day of Public Humiliation, Fasting and Prayer” — a day where all their confidence was to be “reposed only on that God who rules in the Armies of Heaven, and without whose Blessing the best human Counsels are but foolishness — and all created Power Vanity.”14 America continued to humble herself before God and show her reliance upon Him throughout the war. Frequent days of prayer and fasting were observed, not only by individuals and local churches, but also by the Continental Army, and all the newly united States of America. Immediately after the Continental Congress approved the Declaration of Independence, they appointed chaplains to Congress as well as ordering chaplains to be provided for the army. These chaplains were paid with public funds.

As God’s people and the nation humbled themselves and prayed, He moved mightily on their behalf. He gave wisdom to America to know when and how to respond to the injustices of Britain. He worked Christian character into the American people, her leaders, and her army so they could endure many hardships and not give up their fight for liberty, even in seemingly hopeless situations. He also controlled the weather and arranged events to assure eventual victory for the new nation.

One such miraculous event occurred during the summer of 1776. During the Battle of Long Island, Washington and his troops had been pushed back to the East River and surrounded by the

much larger British army. Washington decided to retreat across the wide East River, even though it appeared doomed to fail. If it did fail, this probably would have marked the end of the war. Yet

the God in Whom Washington and the nation trusted came to their aid. He caused a storm to arise which protected the American army from the enemy, then stopped it so as to allow the Americans to escape. He also miraculously brought in a fog to cover the retreat. In addition, He directed a servant, sent to warn the British, to those soldiers who would not understand him—

German-speaking mercenaries. Thanks to God, 9000 men with all their supplies had miraculously retreated to New York. Here we see, as American General Greene said, “the best effected retreat I ever read or heard of.”

This event was so astonishing that many (including General Washington) attributed the safe retreat of the American army to the hand of God.15 On October 17, 1777, British General Burgoyne was defeated by Colonial forces at Saratoga. Earlier, General Howe was supposed to have marched north to join Burgoyne’s 11,000 men at Saratoga. However, in his haste to leave London for a holiday, Lord North forgot to sign the dispatch to General Howe. The dispatch was pigeon-holed and not found until years later in the archives of the British army. This inadvertence, plus the fact that contrary winds kept British reinforcements delayed at sea for three months, totally altered the outcome at Saratoga in favor of America.16

In response to the victory, the Continental Congress proclaimed a day of thanksgiving and praise to God. In part, they stated,

“Forasmuch as it is the indispensable duty of all men to adore the superintending providence of Almighty God, . . . and it having pleased Him in His abundant mercy not only to continue to us the innumerable bounties of His common providence, but also to smile upon us in the prosecution of a just and necessary war for the defence and establishment of our inalienable rights and liberties, particularly in that He hath been pleased . . . to crown our arms with most signal success: it is therefore recommended . . . to set apart Thursday, the 18th day of December, for solemn thanksgiving and praise.” They recommended for everyone to confess their sins and humbly ask God, “through the merits of Jesus Christ, mercifully to forgive and blot them out of remembrance” and thus He then would be able to pour out His blessings upon every aspect of the nation.17

This is the official resolution of our Congress during the Revolutionary War! No wonder the blessings of God flowed upon this nation. Similar resolutions were also issued by the Commander of the American army, George Washington.

When Benedict Arnold’s treason was providentially discovered in September of 1780, both Congress and Washington acknowledged it was by the Hand of God. Congress declared December 7, 1780, a day of Thanksgiving in which the nation could give thanks to God for His “watchful providence” over them. In a letter to John Laurens, Washington wrote, “In no instance

since the commencement of the War has the interposition of Providence appeared more conspicuous than in the rescue of the Post and Garrison of West Point from Arnold’s villainous

perfidy.”18 In Washington’s official address to the Army announcing Arnold’s treason, he stated, “The providential train of circumstances which led to it [his discovery of Arnold’s

treason] affords the most convincing proof that the liberties of America are the object of Divine protection.”19 This Divine protection of the liberties of America was seen over and over again during the Revolution — at Trenton and the crossing of the Delaware; during the winter at Valley Forge; in France becoming America’s ally; during the miraculous retreat of the Americans from Cowpens; and at the Battle of Yorktown.20

Throughout all these events America consistently gave thanks to Almighty God, humbled herself before Him, and sought to obey Him in all spheres of life. This released the blessings and

grace of God upon this nation which enabled America to be victorious in her struggle for freedom. Some years later, God’s grace provided wisdom to establish the United States Constitution, and in so doing provide a Christian form of government through which the Christian spirit of this nation would effectively flow. For America to continue to be a citadel of liberty and prosperity, we must continually humble ourselves before Him who gave birth to this nation and acknowledge with George Washington in his first inaugural speech of April 30, 1789, that,

“no people can be bound to acknowledge and adore the Invisible Hand which conducts the affairs of men more than the people of the United States. Every step by which they have advanced to the character of an independent nation seems to have been distinguished, by some token of providential agency.”21

In 1787, a committee of all the states of the United States of America, gratefully looking back over all the preceding years, set apart October 19, 1787, “as a day of public prayer and thanksgiving” to their “all-bountiful Creator” who had conducted them “through the perils and dangers of the war” and established them as a free nation, and gave “them a name and a place among the princes and nations of the earth.” In that official proclamation they wrote that the “benign interposition of Divine Providence hath, on many occasions been most miraculously and abundantly manifested; and the citizens of the United States have the greatest reason to return their most hearty and sincere praises and thanksgiving to the God of their deliverance, whose name be praised.”22 God is the One who laid the foundation for America and the One Who assured her birth and growth as a nation. Apart from His continued influence, we cannot expect our nation to be maintained.

For PDF Version: Supernatural Transformation via the Bible

By Stephen McDowell

An Excerpt from The Bible: Divine or Human? Evidence of Biblical Infallibility and Support for Building Your Life and Nation on Biblical Truth

Following the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, a group of American pilots known as the Doolittle Raiders were sent to bomb Japan. Some of them were shot down, captured, and put in prison, where they suffered greatly. They were given meager food, so little that some slowly starved to death. They were kept in dark, cold, small cells; they were yelled at, beaten, and kicked. Many became diseased and received little care. The anger and hatred toward the guards due to the tortuous conditions consumed many of the prisoners. This went on for two years.

After one prisoner died from starvation, Bob Hite wrote a letter to the prison governor complaining of their intolerable treatment, reminding him it was against all Geneva conference rules. Among other things, he wrote: “If you can’t do anything useful, will you please give us the Holy Bible to read?”[1] He intermittently attended church growing up, though really knew little of the faith or the Bible. None of the other captives were true believers, and some were even put off by Christianity.

His letter may have done some good, as afterwards their rations improved and they were allowed to share a few books, one being the Bible. They decided to let each man read the Bible for three weeks before passing it on.

Bob Hite said: “it was the first time that I had ever – I think any of us – the first time any of us had really read the Bible from cover to cover. I was sort of like a man being in the desert and finding a cool pool….Instead of hating this enemy that we had such hate for, we began to feel sorry for them….It was almost a miracle to realize the sort of thing that happened to us…we were no longer afraid to the extent that we had been…we no longer had the hatred.”[2]

Just prior to having his turn with the Bible, one of the prisoners, Jake DeShazer, was yelled at by a guard. Rage had been growing within Jake over his two years of imprisonment, so without thought he yelled back. The guard hit him on the head with his fist. Jake kicked him back, with the guard responding by hitting him with his steel scabbard. Jake then threw a bucket of dirty mop water that he had been using to clean the floor on the guard. Oddly the guard only yelled back. “It is strange that he didn’t cut off my head,” Jake said.[3]

Just after this incident the Bible was passed on to Jake. This experience would turn his life upside-down. He began to read the small print from the dim light coming through the small vent at the top of the cell. “The words of the page came to life. It seemed as though they were written just for him.” In the stories he read in the Old Testament and especially in “the story of Christ’s suffering in the New, he felt that God was indeed present, reaching out for someone abandoned, as mistreated, as hopeless as he was.”[4] In his three weeks with the Bible, he spent every minute reading and memorizing all he could.

“On June 8, 1944, he read for a second time Romans 10:9: ‘That if thou shalt confess with thy mouth the Lord Jesus, and shalt believe in thine heart that God hath raised him from the dead, thou shalt be saved.’ Jake prayed: ‘Lord, though I am far from home and though I am in prison, I must have forgiveness.’ As he prayed constantly, thinking deeply about the message of the Bible, he was overcome with a tremendous sensation: ‘My heart was filled with joy. I wouldn’t have traded places with anyone at that time. Oh, what a great joy it was to know that I was saved, that God had forgiven me my sins….Hunger, starvation, and a freezing cold prison cell no longer had horrors for me. They would only be for a passing moment. Even death could hold no threat when I knew that God had saved me. Death is just one more trial that I must go through before I can enjoy the pleasures of eternal life. There will be no pain, no suffering, no loneliness in heaven. Everything will be perfect with joy forever.’”[5]

The central message of the Scriptures became real and alive to him. In the midst of the worst of conditions, he experienced a supernatural contentment only possible in Christ. There is no worldly explanation for this supernatural transformation. It affirms the divine nature of the Bible.

The more he read the more he realized he needed to change deep down inside. He especially needed Christian love. He felt that while his sins had been forgiven through Christ, he would need to forgive as well. A test soon came his way. One day while returning from exercise, the guard yelled at him to hurry, slapped him, pushed him into his cell and slammed the door on his bare foot breaking some bones. As he sat on the stool, anger beginning to rise, he thought God was testing him somehow in this.

The next morning when the guard was back, he first considered revenge but remembering the lesson, responded by saying “good morning.” The guard looked at him strangely since he had never heard Jake say this. Morning after morning Jake tried to be polite and friendly. Finally, the guard came over to him and spoke. Jake asked about his family. This was the beginning of a complete change of treatment from this one guard. From then on the guard treated Jake well, even bringing him food. “I knew then that God’s way will work if we really try, no matter what the circumstances.”[6]

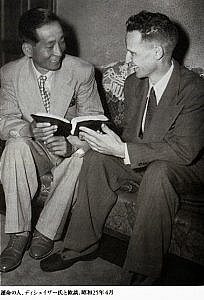

DeShazer was held captive for about one more year, during which time God did other miracles to keep him alive. After the war, Jacob DeShazer and his wife would serve as missionaries to Japan for 30 years. Through their ministry many Japanese were converted, including two of the guards at his prison, and 23 new churches were started. He also worked closely with Mitsuo Fuchida, who had led the air attack on Pearl Harbor, and after the war became a Christian.[7]

Similar stories to that of Bob Hite and Jacob DeShazer have been repeated hundreds of millions of times since Jesus Christ, the living Word of God, came into the world. The supernatural transformation of men who hear its message shows us that the Bible is powerful. The Bible is unique among all books ever written. It is more than the mere words of men. It is in fact divine. The Bible is God’s Word and it is infallible.

To learn more, order a copy of The Bible: Divine or Human? Evidence of Biblical Infallibility and Support for Building Your Life and Nation on Biblical Truth from providencefoundation.com

[1] Craig Nelson, The First Heroes, the Extraordinary Story of the Doolittle Raid – America’s First World War II Victory, Penguin Book, 2003, p. 303.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid., p. 304.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid., p. 305.

[7] See Nelson, pp. 342, 347 ff.

Two hundred years ago this summer the Lewis and Clark expedition embarked on its famous journey. Almost every book and article ever written on this historical event either ignores or significantly minimizes the religious or providential aspects of it. People would be surprised to know that on the day before they departed the St. Louis area in May 1804, most of the men went to church together, and that in August 1804 Meriwether Lewis himself preached a sermon to his men. This essay will highlight some of the influence of faith on the Corps of Discovery. The journals and letters of the members of the expedition were intended to keep records of scientific and historical matters, yet occasionally the faith of these men appears in these records. B efore examining their words, it is helpful to first look at the religious background of expedition leaders Lewis and Clark.

efore examining their words, it is helpful to first look at the religious background of expedition leaders Lewis and Clark.

A little known fact about the Central Virginia Piedmont that gave rise to Lewis and Clark was the dominance of Evangelical revivalism. Even with the disruption caused by the War for American Independence, religious revival in this frontier region was virtually continuous from 1741 to 1789 and resumed briefly again in the first half dozen years of the 19th century (1800-1805).[1]

William Clark, born in nearby Caroline County in 1770, grew up in the Anglican/Episcopal Church. Meriwether Lewis, born in Albemarle County four years later, also grew up attending the Anglican/Episcopal church. His mother Lucy Meriwether was known as “a devoted Christian.” When his father William went off to serve in the Revolutionary War and eventually died in 1779, Meriwether’s uncle Nicholas Lewis of “the Farm” became guardian of the toddler. Earlier in 1777 Nicholas Lewis and the Marks family (Hastings and Peter) were founding members along with Thomas Jefferson of a new independent Calvinistical Reformed Church. It was led by Rev. Charles Clay and met in the Albemarle County Courthouse. Lucy married Peter Mark’s brother John in 1780. Therefore it is likely that Lewis also attended this church from 1777 until 1783 when the family moved to Georgia. Rev. Clay was a central leader of the Great Awakening during these years.

Charles Clay was a product of the Great Awakening. He began ministry as an Anglican priest but, unlike most in Virginia, he was privately trained for the ministry by revivalist leaders and preached in a highly Evangelical manner that Episcopal historian Bishop Meade said was unusual for the times. His Calvinistical Reformed church in Charlottesville drew people from both Episcopal and Presbyterian traditions who had an affinity for Evangelical revival preaching. However the church folded at the end of the Revolutionary War due to economic hardships.

But revival continued to be experienced in various denominations. In 1784 the Methodist Episcopal Church was formally established as a denomination separate from the Anglicans, and in 1785-86 one of its superintendents Thomas Coke preached near “Charleville,” where in his journal he says he “met by our valuable friend, Brother Henry Fry.”[2] Henry Fry, who had previously been an Albemarle Burgess, served as the Methodist circuit rider preacher for Albemarle, Orange and Culpeper Counties, while also tutoring and practicing law. By 1788 a permanent pastor was established at Maupin’s Meeting House not far distant from Meriwether’s home.[3]

The local Presbyterian revival leader was James Waddell who in 1785 moved to the area and preached regularly a few Albemarle locations: at the courthouse in Charlottesville, at the Milton meeting house east of town near Monticello, but especially at the D. S. Meeting house not far from Meriwether’s home. (He also preached in Orange County) Waddell was an outstanding revivalist orator.

The Baptists also had thousands converted and baptized especially due to evangelists John Waller and John Leland. Leland, based out of Louisa’s Goldmine Baptist Church, reported that he had personally baptized 400 people in 1787 and 1788 alone. Leland said that the revival included unusual phenomena and was “very noisy. The people would cry out, `fall down’, and, for a time, lose the use of their limbs; which exercise made the bystanders marvel… Many being convinced…that God was with them…” He said that “in some places singing was more blessed among the people than the preaching was… I have traveled through neighborhoods and counties…and the spiritual songs in the fields, in the shops and houses, have made the heavens ring with melody over my head…”[4] Commenting on blacks in the revival, Leland said: “It is nothing strange for them [i.e. slaves] to walk twenty miles on Sunday morning to meeting, and back again at night.”[5]

It is also important to note that these primary revival leaders – Fry, Waddell and Leland – were also prominent in politics. Leland’s mobilization of Baptist voters was largely responsible for James Madison’s victory over James Monroe in the election for Congress in 1789. Leland led the way in pushing for religious freedom in Virginia and the passage of the First Amendment to the Constitution before he moved to New England in 1791 and continued his efforts there.

All of this religious history is important to note because the very year that this multi-denominational awakening hit its high point in 1787 the 13-year-old Meriwether Lewis moved back to the area from Georgia. He began to study under three tutors of which two of them were the revival leaders Waddell and Fry. His third tutor was Episcopal minister Matthew Maury who ministered in Charlottesville and the northern half of the county.[6] Lewis was a student under Maury in 1788 and 1789. Over the next few years (1790-92) Lewis had Waddell and Fry as tutors at the very time that they were leading interdenominational revival services along with Episcopalians in the area.[7]

In 1792 William Clark wrote a relative saying that he would be honored to be a sponsor at a Christening. This is a religious act that requires membership in a church and is evidence of Clark’s faith. Clark’s home was now in Kentucky.

When about 18 years of age Lewis (in 1792) expressed to Jefferson an interest in leading an exploration some day to the Pacific coast. In 1796 Lewis became good friends with William Clark while serving in the Army together.

In the spring of 1801 Jefferson became President of the United States and asked Lewis to be his private secretary. Lewis moved into the White House with Jefferson in Washington, D.C. These two men attended worship services regularly in the Capitol building and in other Federal buildings, schools, etc. Rev. Manasseh Cutler, a staunch Federalist Congressman and political opponent of Jefferson, reluctantly admitted that Jefferson and Lewis “constantly attended public worship in the Hall.” Cutler’s journal provides the following evidence:

On January 1, 1802 former Albemarle resident and now New England Baptist preacher, John Leland, visited Jefferson and Lewis in the White House and preached a sermon there. Leland presented a mammoth cheese as a gift and also preached to Congress. (Exactly one year later Jefferson and Lewis met and heard Leland preach again in Congress.)

In the 1802 visit Leland returned to the Baptists of Danbury, Connecticut with a $200 donation and a letter from Jefferson that is now famous for affirming a Constitutional “wall of separation between church and state.” This separation was only applicable to the states for Jefferson clearly did not refrain from promoting religion in federal territories under his direct jurisdiction. For instance on April 26, 1802 he signed an Act granting land to the Society of the United Brethren for the Propagating the Gospel among the Heathen. This government support began back in 1787 to help the Moravians in Pennsylvania in “civilizing the Indians and promoting Christianity.”

In 1802 from May 8-27 and again from July 25 to the end of September Jefferson and Lewis visited Albemarle and there they decided that Lewis would command an expedition to the Pacific. In 1800-02 Clark and York traveled frequently from Kentucky to Virginia.

It is likely that they were participants in or at least were aware of what became known as the Second Great Awakening in America. It had its high point in 1801 especially in Kentucky in the form of multi-denominational camp meetings. They were the biggest news on the frontier at the time. In these popular open-air gatherings, hundreds and even thousands of people would gather for five or six days to hear preaching from a variety of ministers. The Central Virginia Piedmont was also a scene of such activity. Sometime in 1802 Lewis’ old tutor, Methodist Rev. Henry Fry organized an outdoor religious camp-meeting at Milton near Monticello where 50 people were converted. Fry was the revival leader for all of the Albemarle, Orange, and Madison area.[9]

The second highest number of converts in all of Virginia that year occurred in none other than Albemarle County. Between 1801 and 1806, there were more camp meetings in Albemarle County than in any other single county in the entire Commonwealth of Virginia.[10] Jefferson’s home county was the hotbed of revivalism.

Historian Carlos Allen notes that indeed “these camp meetings were attended by all ranks of society…”[11] Although it is not known if Jefferson or Lewis attended any of these outdoor camp-meetings, we do know that during these years for the first time in his life Jefferson began to overtly express in several letters that he was “a Christian.” Jefferson’s personal overseer at Monticello, who lived there for thirty years, spoke of seeing him at the White House with his Bible: “(There was) a large Bible which nearly always lay at the head of his sofa. Many and many a time I have gone into his room and found him reading that Bible.”[12] Indeed, Jefferson, perhaps more than any other President, studied the Bible devotedly.[13]

In 1803, Jefferson wrote to the devout Evangelical Doctor Benjamin Rush saying: “My views are very different from that anti-Christian system imputed to me by those who know nothing of my opinions. To the corruptions of Christianity I am indeed, opposed, but not to the genuine precepts of Jesus himself. I am a Christian…”[14][15] In this Jefferson was articulating the popular Evangelical sentiment on the Piedmont frontier at the time. These views were held by what was known as the Restoration or Primitive movement – Evangelical revivalists who opposed anything not explicitly found in the Bible; and opposed to all organized religious systems and priests that added to it. They wanted to restore Christianity back to as it was in the early centuries.

A couple years later one of these camp meetings was held again at Milton and drew four thousand people to a place called “Sharp’s Campground.” The evangelist was Lorenzo Dow–America’s most prolific camp meeting preacher during the Second Great Awakening. Dow’s own journal confirms that even members of the Jefferson family attended his meetings. Dow wrote: “I spoke in… Charlottesville near the President’s seat in Albemarle County; I spoke to about four thousand people, and one of the President’s daughters who was present [on 17 April 1804], died a few days after.”[16] (Jefferson was at Monticello from Apr 4-May 11). This daughter was Mary Jefferson Eppes whose husband John was a Republican Congressman. Following her death, Jefferson’s other daughter Martha “found him with the Bible in his hands (seeking)… consolation in the Sacred Volume.”[17]

Within the next month or so Jefferson corresponded with Rev. Fry who organized these meetings and in the letters between them (Jefferson’s were dated May 21 and again June 17) it is evident that Jefferson met with Fry. On Feb 26, 1805 Rev. Henry Fry writes another letter to Jefferson which is delivered in person to Jefferson by Rev. Lorenzo Dow in Washington City probably about a week or so later. Dow had been visiting the Albemarle area before that. (Later in the year Dow carried diplomatic papers to Europe for Madison.).

This evidence along with the relationship Leland and other Evangelical leaders had with Jefferson and Lewis is important background for understanding the religious element in the Lewis and Clark Expedition. These facts are either not known to or not reported by most modern biographers of Jefferson and Madison.

One Jefferson biographer writes that Jefferson especially “gave liberally to missionary purposes, and in his account books we find frequent entries of sums of money paid towards the support of churches, missionaries, and religious schools.”[18] He gave to “missionaries” in 1792 (and on May 20, 1806, Jefferson personally “gave 50 dollars to [the] Governor of Louisiana for building a church there.”)[19]

Jefferson corresponded six times in the 1790s with Mr. Dowse of Massachusetts who apparently understood Jefferson’s interest in Christian missions to the native Americans in a way that many modern scholars have dismissed as irrelevant. William Linn, a Presbyterian minister in New York, wrote three letters to Jefferson a few years earlier in 1797 and 1798, urging him to use his influence as Vice President of the United States to encourage evangelism and education of the Indians.[20] In 1800 Jefferson wrote to Rev. Samuel Miller who was asking for the Vice-President’s assistance in such missionary work. Jefferson’s Memorandum Books show that he consistently donated his own money to missionaries and to societies that shared these goals.

As was already stated, in April 1802, Jefferson signed into law the Act of Congress which funded the Society of the United Brethren “for Propagating the Gospel Among the Heathen” in the Northwest Territory. In 1803, he purchased the Louisiana Territory from France that doubled the size of the United States and multiplied the number of unreached Indian tribes in America’s jurisdiction. Jefferson then proposed three treaties with Indian tribes that included Federal money for constructing churches and paying salaries of missionaries and clergymen – the first of which was in October 1803. In April of 1803, Edward Dowse sent President Jefferson a copy of a sermon by Rev William Bennet, The Excellence of Christian Morality, and spoke about the importance of promoting the “extension of civilization and Christian knowledge among the Aborigines of North America.” Dowse said that “it seemed to me to have a claim to your attention: at any rate, the idea, hath struck me that you will find it of use; and, perhaps, may see fit, to cause some copies of it to be reprinted, at your own charge, to distribute among our Indian Missionaries.”[21] On Apr 19 Jefferson replied to Dowse and expressed his longing for a compilation (for distribution to the Indians?) of “the moral precepts of Jesus…freed from the corruptions of latter times” due to “a priesthood…(that) twist it’s texts till they cover(ed) the divine morality of it’s author.”

In early 1804 Jefferson took “one or two evenings” while in the White House to cut out of two New Testaments the teachings of Jesus Christ alone without any biographical material or narrative included.[22] At first, Jefferson asked Rev. Joseph Priestley to make this: “digest of [Christ’s] moral doctrines, extracted in his own words from the Evangelists, and leaving out everything relative to his personal history and character.”[23] When Priestley suddenly died Jefferson went ahead and compiled what he titled: “The Philosophy of Jesus of Nazareth from the account of his life and doctrines as given by Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. Being an abridgement of the New Testament for the use of the Indians unembarrassed with matters of fact or faith beyond the level of their comprehensions.” This was after he had received letters from “McPherson, et al” that urged his support of missions to Indians by helping encourage the dissemination of Bibles in their languages. His abridgement was perhaps in response to this request.

Henry Randall’s biography of Jefferson states that he “conferred with friends on the expediency of having it published in the different Indian dialects as the most appropriate book for the Indians to be instructed to read in.” This comment by an early biographer suggests the possibility that Jefferson even hoped to have some of his abridgements printed in time for Lewis and Clark to take with them on their expedition to explore the new Louisiana Territory (which came into American possession in January). By making a brief compilation of Jesus’ teachings, Jefferson felt that it would not only be easier to understand, but it would be more easily translated into the multitude of Indian dialects and printed in larger quantities at less cost than whole Bibles. In this light, therefore, Jefferson’s first abridgement of the Gospels was clearly intended primarily for an evangelistic and educational purpose in the Christian schools on the frontier. The dismissal by modern scholars of Jefferson’s genuine interest in Christian missions to the Indians has led to the misunderstanding of Jefferson’s motives for his earliest compilation of Christ’s teachings.[24] This is the mistake made by Dickinson Adams in an otherwise excellent study of Jefferson’s abridgement. Adams unfortunately ignored all the local background evidence and, basing everything on one comment that Jefferson made concerning his second inaugural address in 1805, asserted that “the subtitle of ‘The Philosophy of Jesus’ was deliberately ironic and that the work itself was never intended specifically for the aboriginal population.”[25]

It is also worth noting that when Jefferson did this abridgement for the Indians he wrote that it would be “unembarrassed with matters of fact or faith beyond the level of their comprehensions.” His motivation was comprehension, not unbelief, when he decided on some “matters of fact” to be left out. However, simply because he first asked the Unitarian Rev. Joseph Priestley to prepare the abridgement, some scholars have erroneously claimed that Jefferson’s motives were that he did not believe in the rest of the Bible.[26] But Jefferson’s Memorandum Books show that in 1804 and again in 1814 he made personal donations to Bible societies that distributed the whole book to the poor in his own state.[27]

Although Jefferson had not originally mentioned religion in his plans for the expedition, on April 17, 1803, Jefferson received a letter from his Attorney General Levi Lincoln that recommended the expedition also help Christian missions by studying what the Indian tribes believed about “a supreme being, their worships, their religion” and “the probability of impressing their minds with a sense of an improved religion and morality and the means by which it could be effected.”[28] Lewis probably handled this correspondence for Jefferson and since he would be leading the expedition, took the advice seriously. For instance in April and May Lewis went to Philadelphia and there spent time with Benjamin Rush and discussed the “morals and religion” of the Indians (among other things).

When Jefferson made his final Instructions to Lewis on June 20, 1803 he said: “The object of your mission is to… acquire what knowledge you can of the state of morality, religion, and information among them as it may better enable those who may endeavor to civilize and instruct them, to adapt their measures to the existing notions and practices of those on whom they are to operate.” Jefferson also added his “sincere prayer for your safe return.”[29]

The people who Jefferson described as “those who may endeavor to civilize and instruct them” were missionaries of the various religious denominations. Jefferson wanted the expedition to prepare the way for missionary efforts among other things. It is also notable that Jefferson added “my sincere prayer for your safe return.” President Jefferson in prayer for the Lewis and Clark expedition is not a fact one usually ever hears discussed.

Indian missions had been a consistent interest of Jefferson as various treaties and federal initiatives under his administration reveal. For instance, in late October of 1803 Jefferson presented to Congress a Treaty with the Kaskaskia and other Tribes (northwest of the Ohio River in present-day Illinois) that transferred their country to the U.S. and also said that “the United States will give, annually, for seven years, one hundred dollars towards the support of a priest of that religion (Roman Catholic),…who will also instruct as many of their children as possible;…And the United States will further give the sum of three hundred dollars, to assist the said tribe in the erection of a church.” This treaty was likely already known to Lewis when he arrived with William Clark and a handful of men at Kaskaskia army post (in present-day Illinois) on November 28.

Jefferson consistently supported federal governmental aids to missions. On April 23, 1803 Jefferson sent a letter to Secretary of War Henry Dearborn instructing that $300 in federal money be appropriated for Rev. Gideon Blackburn’s school for Cherokees in Tennessee. (Jefferson had just recently met with this Presbyterian minister.)

Jefferson’s support of religious interests in the federal territories also is evident in his response a few months later to the Ursuline Nuns in New Orleans. On May 15, 1804 Sister Therese Farjon, the superior of the Catholic convent wrote a Letter to President Jefferson to inquire about the impact of the new control of America’s government over the territory of lower Louisiana. Jefferson replied to them by quoting from Biblical book of Proverbs chapter 22, verse 6. He also said that “The principles of the Constitution and government of the United States are a sure guarantee to you…that your institution will be permitted to govern itself according to its own voluntary rules and without interference from civil authority;….Your institution…by training up its young members `in the way they should go’ cannot fail to ensure the patronage of the government it is under. Be assured that it will meet with all the protection my office can give it.”[30]

His promise of government patronage of a religious institution in a federal territory was not inconsistent with his other acts and views as he expressed concerning church and state. As Jefferson explained in his Second Inaugural Address in 1805 and in a letter to Rev. Samuel Miller in 1808 governmental promotion of religion in federal territories was permitted by the Constitution. It was only among the states that the federal government could not promote or interfere in religious affairs. His primary guiding principle in affairs of church and state was not secularism, but federalism – not separation of religion from all government, but rather separation of the federal government from the decisions of state governments in regards to religion. As the First Amendment stated: “Congress shall make no law establishing religion” but that did not prevent the President or state legislatures from acting.

Even when Jefferson personally welcomed Indian delegations to Washington he did not leave out the religious element. On July 12 & 16, 1804 a delegation of 14 Osage chiefs from Missouri met with Jefferson. He said to them in this official address: “I thank the Great Spirit who has inspired you…and who has conducted you in safety (to us);…The Great Spirit has given you strength, and has given us strength; not that we might hurt one another, but to do each other all the good in our power…May the Great Spirit look down upon us, and cover us with the mantle of his love.”[31]

On June 4, 1805 the nation of Tripoli signs a Peace Treaty with U.S. in which Jefferson’s government had deleted the phrase in an earlier treaty that denied the connections of Christianity to the U.S. government.

Among the members of the expedition chosen by Lewis and Clark there were certainly some who were devout religious men. Various sources clearly identify that some were Protestants including Lewis, Clark, George Shannon and William Bratton. John Shields was known to be a Baptist. William Bratton was a man of strict morals due to his faith. Some corps members were of the Roman Catholic faith: Francois Labiche, Jean DeChamps, Jean LaJeunnesse, Toussaint Charbonneau, Sacagawea, Charles Hebert, and Peter Pinaut. There were certainly others who held religious beliefs, but we simply do not know of what specific denomination. For instance, it is known that on the morning of the corps’ departure (May 20, 1804) about two-thirds of the men worshipped and prayed together in the village of St. Charles (now in Missouri).

On that day Lewis wrote in his journal that the St. Charles “village contains a chapel” and that the people “live in a perfect state of harmony among each other, and place an implicit confidence in the doctrines of their spiritual pastor, the Roman Catholic priest.”[32] The church was called St. Charles Borromeo and the priest was Rev. Lusson.[33] Clark wrote that “It is Sunday, and twenty men went to church today;…Send 20 men to Church today;…Most of the party go to the Church;[34]…I gave the party leave to go and hear a Sermon today delivered by Mr. _______, a Roman Catholic Priest.”[35] Being a French colony from its inception, there had yet to be established a Protestant church in the area.

One of these expedition members was Private Joseph Whitehouse who also wrote on that day that “several of our party went to the Chapel, where Mass was said by the Priest, which was a novelty to them.”[36] The reference to a “novelty” referred to the Mass and Roman Catholic liturgy since most of the men were Protestants. Such liturgy was truly new for them, but they put aside their sectarian preferences for the opportunity to attend church together before they departed on their journey. Sergeant Ordway recorded in his journal that he attended this service.

Since Jefferson’s Instructions to Lewis said that “the object of your mission is to… acquire what knowledge you can of the state of morality, religion…among (the Indians)…” The expedition’s meetings with Native-Americans therefore had an important religious component. This was evident in the Corp’s first Indian council which took place on August 18, 1804 with 7 Oto chiefs across from what is today Council Bluffs, Iowa. First there was a full uniform dress parade of the soldiers with cocked hats. Then Lewis and Clark delivered a message to the Oto Indian chiefs in behalf of the great Chief of the Seventeen nations of America (i.e. President Jefferson). It closed with a religious expression by saying: “We hope that the great Spirit will open your ears to our councils, and dispose your minds to their observance…(and) smile upon your nation.”[37] This type of religious expression from Lewis and Clark (representing Jefferson) was prominent and consistent throughout the journey. It showed an earnest desire to relate commonly in language and devotion with the Indians.

Americans were, of course, not the only ones to have a faith in God. The Indians had a strong religious expression as noted in the journals. There are many references in the journals to Indian burial mounds, relics, monuments and practices, but a first hand experience occurred on August 13, 1805. Lewis and a few of his expedition met some Shoshoni Indians who took them to their village where he heard the people called the Corps the “children of the Great Spirit.”[38] This willingness of the Indians to associate the Corps with God was critical to the survival of the expedition. It shows the religious devotion of Native-Americans – an important religious element of the Lewis and Clark expedition to be remembered as well. When two days later some of the Indian men decided to depart with the Corps to attempt to find the rest of them, Lewis said that the Indian villagers were “imploring the Great Sperit” for protection of their men.[39] They also believed in prayer.

Probably Lewis’ most overt religious expression throughout the journey among his own men was at the funeral of Sergeant Charles Floyd two days after the Indian council. When Floyd died from a ruptured appendix on August 20th Clark wrote that “Capt. Lewis read the funeral Services over him.”[40] Private Whitehouse elaborated in his journal and said that a “funeral ceremony” was “performed” and there was a “sermon preached over him.”[41] This reference, along with Clark’s, suggests that apparently the person who preached this sermon was Lewis.

Although nothing is said in the journals about their religious devotions on Christmas, the Corps did not fail to do something to acknowledge the day of the birth of Jesus Christ. In 1804 they celebrated by firing 3 cannon and raising a flag.[42] There was no reason to do these things among themselves in the wild if it did not arise out of the sincere devotion of many of the men.

Evidence of belief in a God who answers prayer is seen whenever a person is in danger and needs help beyond human reach. Although little comment is made about it, Lewis records examples of his men crying out to God. For instance, on May 14, 1805 Lewis notes that Charbonneau cried out to God for mercy when the pirogue he was steering capsized. A few weeks later on June 7, 1805 Lewis and Richard Windsor almost fall off a slippery cliff. Lewis noted that Windsor cried out to God twice while barely hanging on.[43] Even without the threat of danger there is also evidence of his men’s simple thankfulness to God when Lewis notes on August 12, 1805 that Hugh “McNeal…thanked his God that he had lived to bestride the mighty and heretofore deemed endless Missouri (river).”[44]

On Aug 17, 1805 the expedition experienced perhaps its most critical danger. Lewis and a few men were separated from the rest of the corps when they encountered some Shoshoni Indians. When Lewis was finally permitted to search for the rest of the corps and found them, there they discovered that the chief was Sacagawea’s brother. Potential disaster was turned into favor and assistance beyond all expectation so that they could cross the Rocky Mountains. Such evidence of divine providence induced the Corps to name that place “Camp Fortunate.”

When the Corps finally reached the Pacific coast they set up camp and on December 25, 1805 Clark wrote that they celebrated “this day, the Nativity of Christ.”[45] They sang (worship?) and fired their guns. Whitehouse wrote of their exchange of gifts “in remembrance of Christmass” and recorded the only statement of faith on their entire behalf. Apparently summarizing statements made by most of the men on that day, Whitehouse wrote that “the party are all thankful to the Supreme Being, for his goodness towards us – hoping he will preserve us in the same, and enable us to return to the United States again in safety.”[46] By claiming that all of the party felt this way, Whitehouse suggests to the reader that at least all of the Corps were believers in God and that they held to a view that He rules over human affairs and their endeavors in particular. They apparently had expressed a sort of group prayer for God’s help to return home safely. This prayer was obviously answered.

Clark gave his most eloquent statement of faith a couple weeks later on Jan 8, 1806 when he wrote of the provisions they obtained from a beached whale. Referring to the story in the Biblical book of Jonah, he said that: “I… thank Providence for directing the whale to us; and think Him much more kind to us than He was to Jonah having sent this monster to be swallowed by us, instead of swallowing of us, as Jonah’s did.”[47] This expression of faith by Clark also shows that he had some degree of knowledge of the Scriptures.

In early 1806, while the Corps was making its way eastward again, President Jefferson’s Letter to the Chiefs of the Cherokee Nation in January and then his Treaty with the Wyandot Indians in April continued to show his support for missions. Plus in May President Jefferson sent a personal financial donation to the Governor of the Louisiana Territory residing in St. Louis to help build a church there. This is additional evidence of Jefferson’s consistent interest in the religious life of the new western territory.

The Corps arrived in St. Louis on the 23rd of September 1806 and later dispersed and began to make their way back to their homes. In December Lewis returned to Albemarle (Locust Hill) and then Charlottesville for a celebration dinner at the Old Stone Tavern with about 50 people including Jefferson.

Clark sent a letter to some friends in Virginia on January 8, 1807 expressing a religious devotion in saying that: “Gentlemen we ought to assign the general safety of the party to a singular interposition of providence, and not to the wisdom of those who commanded the expedition.”[48] In other words Clark said their success was none other than a sign of God acting directly in their behalf.

Lewis also expressed himself with some religious devotion after the expedition. For instance, on January 14, 1807 Lewis, at a dinner and ball in Washington, Lewis offered his toast saying: “May works be the test of patriotism as they ought, of right, to be of religion.”

Lewis also visited Jefferson at Monticello. On May 23 Jefferson support of missions continued with his Treaty with the Cherokee Nation. Then on Nov 3 Jefferson sent a letter to Messrs. Thomas, Ellicot, and the Society of Friends in response to one from them in October. Jefferson wrote that the principles of his government were “dictated by…the precepts of the gospel;…(and that) the same philanthropic motives have directed the public endeavors to ameliorate the condition of the Indian natives; …In this important work I owe to your society an acknowledgement that we have felt the benefits of their zealous co-operation, and approved its judicious direction …as preparatory to religious instruction and the cultivation of letters.” Jefferson also ended it by “sincerely pray(ing to)…the Father of us all.”

Then in January of 1808 Jefferson’s letter to Rev. Samuel Miller explained the First Amendment and his understanding of how religion relates to government on the state and federal level. This was in response to a letter from Miller representing Presbyterians in America. Miller was an ardent supporter of Jefferson who had written in previous years urging Jefferson’s support for missions to Indians.

And in Lewis’ letter to William Preston he shows his religious feelings when he said: “May God be with her and her’s, and the favored angels of heaven guard her bliss both here (and) hereafter, is the sincere prayer of her very sincere friend.” (July 25, 1808). On November 16, 1808 Lewis wrote that “I pass cheerfully through that portion of my life which cannot last always, and with resignation wait for that which will last forever.” In August 1809 Lewis said that “I call my God to witness” in a letter to William Eustis. It was the last expression of faith we have of him.

On December 28, 1809 Jean-Baptiste Charbonneau, son of Sacagawea, was baptized in the Catholic Church in St. Louis. It is probably done with Clark’s assistance since he was there at the time.

In 1807 Lewis had asked Rev. William Woods of Albemarle’s Buckmountain Baptist Church to handle the subscriptions for the forthcoming printing of his journals. This showed some relationship with this pastor. When Jefferson retired from the Presidency back to Albemarle this church sent a letter to Jefferson to praise his work. He sent a letter in response on his birthday April 13, 1809 which said that they knew him better than anyone and that they had worked together in politics and religion.

There is also an account in 1831 that Clark, as Superintendent of Indian Affairs in St. Louis, was visited by four Indians from the northwest who came to seek “the book of heaven.” A newspaper report said that Clark introduced them to the Catholic and Methodist church leaders there. The news of this visit sparked the emergence of the missionary impulse that gave rise to the creation of the Oregon Trail and westward settlements.

_________

Mark Beliles is co-founder of the Providence Foundation and was a member of the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial Festival Committee in Charlottesville, Virginia. (This essay was presented as a lecture during the Charlottesville Bicentennial Festival in May 2003. Mark Beliles resides in Charlottesville but has visited sites and research centers associated with the expedition including: Louisville, Kentucky, Clarksville, Indiana, St. Louis and St. Charles, Missouri, as well as sites in Montana, Washington and Oregon, including Fort Clatsop on the Pacific coast.)

[1] Notice the dates given by Wesley M. Gewehr, The Great Awakening in Virginia, 1740-1790 (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1930). However, John B. Boles, The Great Revival, 1787-1805 (Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1972) and Carlos Allen date the start of the Second Great Awakening in the 1780s. I think Gewehr’s dates fit the facts better and the events of 1787 to 1789 should be included in the First Awakening rather than the Second. The Second Awakening did not come in force until around 1800.

[2] Clark, 1:459 (April 1784). See also Warren A. Candler, Life of Thomas Coke (Nashville, Tenn.: Publishing House M. E. Church, Lamar and Barton, Agents: 1923), 96-97. Asbury stayed at Tandy Key’s home again in 1800, 1808, and 1809. See entry from Coke’s journal quoted from 24 May, 1786, cited in Slaughter, Autobiography of Henry Fry, 83. And apparently a black preacher, Harry Hosier, came with Coke.

[3] Woods, 134-135. See also Mary Rawlings, The Albemarle of Other Days (Charlottesville, Va.: Michie Co., 1925), 101 (“The oldest Methodist church in the county was…erected prior to 1788.”).

[4] Isaac, 300. The Writings of the Late Elder John Leland, ed. L. F. Greene, (New York: G. W. Wood, 1845), 105, 115.

[5] Isaac, 307. Greene, 98. Leland said also that “they are remarkably fond of meeting together, to sing, pray, and exhort, and sometimes preach…”

[6] The Anglican revival leader for Virginia, Devereaux Jarratt, declined in health and died in 1801 and the new Bishop in the 1790s, James Madison, was not an Evangelical. Maury (1744-1808) performed the wedding of Thomas Mann Randolph and Martha Jefferson at Monticello in February 1790. He also taught school, and Meriwether Lewis was among his pupils. In Orange County’s St. Thomas Parish, Maury usually helped, but there was also Charles O’Niel from 1797-1800 (With the exception of O’Niel, no resident minister was in this parish from 1774 to 1832). South of Albemarle County, Amherst ministers were John Buchanan in 1780, John White Holt in 1787, Isaac Darneile in 1790; Nelson ministers were William Crawford 1789-1815. Like Maury, Darneile and Crawford also occasionally preached in southern Albemarle County (St. Anne’s Parish) during these years. Brown, 26-27.

[7] William Foote, 428. Foote fails to report any of this and the reader tends to believe that revival did not exist in areas north of the James River. In fact, he also implies that these churches were worldly because the Presbytery in 1791 heard accusations against them (the Reverend Irvin of Albemarle County was one of those charged with sin, but exonerated). See ibid., 433-434. Jan Lewis, The Pursuit of Happiness: Family and Values in Jefferson’s Virginia (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 241, note #21. In an otherwise excellent book, Lewis unfortunately makes the common, yet faulty, assumption that religion in revolutionary Virginia was weak. See 43-44. Diary of Col. Francis Taylor, 1786-1799, (microfilm, University of Virginia Library). During the War of American Independence, Col. Taylor’s Albemarle County Battalion (a.k.a. the Convention Army Guard Regiment) guarded British and Hessian prisoners of war at a camp west of Charlottesville. Gundersen, 197. Fry would “read the service before Balmaine preached.”

8 Claude G. Bowers, Jefferson in Power (Boston, Mass.: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1936), 22-23. Manasseh Cutler, Life, Journal, and Correspondence (Cincinnati, Ohio: Robert Clarke and Co., 1888), II: 72, 114, 118, 119, 172.

[9] Allen, 69-70, 103-104; and William Bennett, Memorials of Methodism in Virginia (Richmond, Va.: self-published, 1871), 489-490. Allen provides one of the few historical accounts of the Great Revival that adequately highlights events in Albemarle County and areas nearby, and gives due attention to its leader Henry Fry. Bennett includes much local history which is, perhaps, due to the fact that he was the pastor of a Methodist church in Charlottesville for a while and had great access to local records and oral histories. See Woods, 135.

[10] Allen, 89-91, 96.

[11] Allen, 78-79. See also: Nathan O. Hatch, The Democratization of American Christianity (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1989), 49.

[12] James Bear, Jr., Jefferson at Monticello (Charlottesville, Va.: University Press of Virginia, 1967), 109-110.

[13] Henry Foote writes that: “It was these ‘simple precepts’ of Jesus which Jefferson sought to compile, not only for his own use but also for the instruction of the Indians in fundamental Christian principles, for he had an interest in and sympathy with the Indians which was shared by few others in his day. About the beginning of 1804 he sent to Philadelphia for two Greek Testaments and two in English, from which to cut the desired passages. And then we have the unique spectacle of a president, whom his enemies denounced as a foe of Christianity, spending his late evenings in the White House, after his company had left, in diligently piecing together passages from the Gospels to make a connected story of the life and teachings of Jesus.” Henry Wilder Foote, The Religion of Thomas Jefferson (Boston, Mass.: Beacon Press, 1963), 61.

[14] Jefferson to Benjamin Rush, 21 April 1803. (see appendix of Adams’ Extracts).

[15] Jefferson to Martha Jefferson Randolph, 25 April 1803. Jefferson also sent at this time two letters to Priestley, 9 April 1803 and 24 April 1803 (both found in appendix of Adams’ Extracts). Jefferson while living in Philadelphia came to know Priestley and Quakers who emphasized the moral teachings of Jesus above doctrinal formulations. Jefferson’s approach to the Bible was similar. See Jefferson to Gerry, 1801.

[16] Peggy Dow, The Dealings of God, Man, and the Devil; as Exemplified in the Life, Experience, and Travels of Lorenzo Dow (New York: Cornish, Lamport and Co., 1852), 87. Dow’s journal entry for this is number 653. Dow also participated in an 1802 campmeeting in Albemarle County.

[17] Randolph, 300.

[18] Curtis, 339.

[19] Memorandum Books, II:884, 1180.

[20] In 1791 Rev. Linn sent Jefferson a printed sermon and Jefferson wrote a letter to thank this Presbyterian minister.

[21] Jefferson to Edward Dowse, 19 April 1803 (in appendix of Adams’ Extracts).

[22] Jefferson to Rev. Francis Vanderkemp, 25 April 1816 (in appendix of Adams’ Extracts). Jefferson sent two other letters to Vanderkemp in 1816: 30 July and 24 November (both in Adams’ Extracts).

[23] Jefferson to Priestley, 29 January 1804 (see appendix of Adams’ Extracts).

[24] Dickinson Adams reconstructed the Philosophy of Jesus…for the Use of the Indians from a table of texts that has survived and by examining the original Bibles that Jefferson used to clip out the texts. This was a valuable contribution to Jeffersonian scholarship for it shows that Jefferson did not take out all of the miracles and evidences of Christ’s divinity in his 1804 abridgement. There were still references to miracles, resurrection, and the second of coming of Christ. Adams’ reconstruction of the Philosophy of Jesus revealed that there were 16 passages that Jefferson clipped from the two New Testaments which were not listed in the surviving table of Scripture texts. Adams included eleven and one half of these passages in his reconstruction but arbitrarily left out two of the others that dealt with the miracles of Christ because of his own assumptions about Jefferson’s bias against it. Matthew 11:4-5 is one of these passages Adams excluded without justification. See Mark Beliles, ed., Thomas Jefferson’s Abridgement of the Words of Jesus of Nazareth (Charlottesville, Va.: self-published, 1993). The following selections are from the Philosophy of Jesus…for the use of the Indians:

[25] Dickinson Adams, 28. Adams said “Indians” was a code word for Jefferson’s Federalist and clerical adversaries, but see Malone, Jefferson the President – First Term 1801-1805, 205, and Henry S. Randall, The Life of Thomas Jefferson, 3 vols. (New York: Derby and Jackson, 1858), 3:654-658. The latter scholars believed that Jefferson’s subtitle was not disingenuous. Adams’ work erroneously concluded that the motivation for the 1804 abridgement and a later 1819 version called The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth was the same. But it was not. Jefferson said that the 1819 abridgement was for his own use whereas the 1804 version was for the Indians. Jefferson expressed nothing clearly unorthodox at the time of the 1804 version but he certainly had adopted a Unitarian and rationalist theology by the time of the latter version.

[26] Jefferson bought at least twelve whole Bibles or New Testaments during his life. Jefferson’s Memorandum Books, II:1522. Jefferson’s personal interest in the Gospels at this time was consistent with Jefferson’s earlier orthodox Religious Notes in 1776 which prioritized the “fundamentals” contained in those books of the Bible more than any others (and yet acknowledging that the rest was still “inspired”).

[27] See Jefferson’s Memorandum Books, II:1297.

[28] Jackson, Donald, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1962), pp. 34-36.

[29] Jackson, pp. 61-66.

[30] Papers of Thomas Jefferson, (Letter to the Ursuline Nuns of New Orleans, May 15, 1804).

[31] Jackson, pp. 199-203.

[32] Moulton, Gary E., ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1990), Vol 2, p.___. Thwaites, Reuben Gold, ed., Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1904), Vol 1, p. 24.

[33] Brown, Jo Ann, St. Charles Borromeo: 200 Years of Faith, (published by St. Charles Borromeo church, 1991), pp 8-30.

[34] Osgood, Ernest Staples, ed., The Field Notes of Captain William Clark, (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1964), p. 43.

[35] Moulton, Vol 2, p.____. Thwaites, Vol 1, pp. 22.

[36] Moulton, Vol 11, p. 10.

[37] Jackson, p. 208.

[38] Moulton, Vol 5, p. 97.

[39] Moulton, Vol 5, p. 97.

[40] Osgood, p. 111.

[41] Moulton, Vol 11, p. 58.

[42] Moulton, Vol 11, pp. 113-114.

[43] Moulton, Vol 4, p. 262.

[44] Moulton, Vol 5, p. 74.

[45] Moulton, Vol 6, pp. 137-138.

[46] Moulton, Vol 11, p. 407.

[47] Moulton, Vol 6, pp. 183-184.

[48] Jackson, pp. 359-360.

By Stephen McDowell

One great factor in the secularization and decline of America is the teaching of revisionist history in our schools. As an example of this, a friend recently wrote me that two American Indian history teachers at Minnesota State University told him that Thanksgiving was the celebration of the massacred 600 Pequot Indians in colonial New England.

Wanting to learn more of why they thought this, my friend found an article that seemed to detail their beliefs, in which is stated:

Ironically, the first official “Day of Thanksgiving” was proclaimed in 1637 by Massachusetts Governor John Winthrop. He did so to celebrate the safe return of English colony men from Mystic, Connecticut. They massacred 600 Pequots that had laid down their weapons and accepted Christianity. They were rewarded with a vicious and cowardly slaughter by their new “brothers in Christ.”[1]

Unfortunately, too many Americans today would readily believe this almost totally false statement. Having read much about these early settlers, and knowing the lies and half-truths that are presented ashistory today, I was able to point out why this statement is wrong.

First, the context of the Pequot Indian war was not as they represent. The Pequots had not laid down their weapons nor accepted Christianity. In reality, they were terrorists who had kidnapped and killed many men, women, and children over the prior years.

The Pequot Indian war was the first European-Indian war in New England. On one side was the greatly feared Pequot tribe, on the other the colonists and the Narragansett, Mohican, and Mohawk Indians. The Pequots (or Pequods) were a hostile tribe who had fought and lorded over other Indian tribes long before Europeans settled in the area. Their hostility was especially shown to the white settlers who first arrived in late 1620. With the influx and inland settlement of new colonists, hostile encounters increased.

In 1633 Pequot warriors murdered the captain and crew (8 men total) of a small Massachusetts vessel trading in the Connecticut River area. After this they massacred some Indians friendly to the Dutch, who had a garrison in the area. The Dutch retaliated by capturing and hanging a few Pequots, who then took up arms against the Dutch. They sought the friendship of the English, and for that purpose sent four or five ambassadors to Boston in November 1634 to negotiate a treaty. In return for their help, which included negotiating peace with their long-time enemy the Narragansett Indians, the Pequots gave them some land in the Connecticut valley and promised to surrender the remaining two murderers of Captain Stone’s party. The leaders of Massachusetts accepted their claim conditionally and then helped reconcile the Pequots and the Narragansetts.

The Pequots, however, never gave up the murderers, nor did they keep the peace with the Englishmen. In fact, they kidnapped children, destroyed or made captive families on the borders of the settlements, and murdered Englishmen they found alone in the woods or on the waters.[2]

In July, 1636, another trader, John Oldham, was murdered and his men carried off by the Pequot Indians on Block Island. At this, “God stirred up the hearts” of Governor Vane and the rest of the magistrates to protect their people.[3] To punish the crime, Massachusetts sent 90 men under the command of John Endicott. This force encountered some Pequots at Block Island and in a brief battle they killed a few Indians and destroyed their wigwams and much property. The Indians fled and Endicott followed them to the mainland. Upon encountering the Pequots, he demanded they surrender the murderers. When they did not, Endicott attacked them, killing a score of them and destroying some of their corn. Such a reprisal only enraged the Pequots, who in subsequent conflicts captured and scalped seven of the Massachusetts men.[4]

Re-enforcements came from Connecticut to assist them in their mission to totally defeat the Pequots and stop the attacks and murders. Showing no signs of remorse, the Pequots sought the alliance of the neighboring Narragansetts and Mohicans (or Mohegans), and continued to murder those whites they came upon. With requests from Massachusetts, Roger Williams traveled alone to the sachem of the Narragansetts to convince him not to align with the Pequots. When Williams arrived, the Pequot ambassadors, “reeking with blood freshly spilled,”[5] were already there. For three days Williams lodged and mixed with them, always fearing for his life. In the end he succeeded in keeping the Narragansetts from joining with the Pequots, who remained alone in the war with the English.

Continued attacks and murders roused Connecticut to action. “All through the winter of 1636-37 the Connecticut towns were kept in a state of alarm by the savages. Men going to their work were killed and horribly mangled. A Wethersfield man was kidnapped and roasted alive. Emboldened by the success of this feat, the Pequots attacked Wethersfield, massacred ten people, and carried away two girls.”[6] To help bring spiritual aid, Boston had declared a Fast Day on January 19, 1637, recognizing the “dangers of those at Connecticut.”[7]

Cotton Mather records this event during this frightening time:

A Pequot-Indian, in a canoo, was espied by the English, within gunshot, carrying away an English maid, with a design to destroy her or abuse her. The soldiers fearing to kill the maid if they shot at the Indian, asked Mr. [Rev. John] Wilson’s counsel, who forbad them to fear, and assured them “God will direct the bullet!” They shot accordingly; and killed the Indian, though then moving swiftly upon the water, and saved the maid free from all harm whatever.[8]

In response to the Pequot atrocities, the leaders of the three infant towns meeting at a General Court (legislature) in Hartford, decreed war on May 1, 1637. They sent 60 to 90 men, one third of the whole colony, under the command of Captain John Mason, and accompanied by Rev. Samuel Stone as chaplain, to attempt to stop the Pequots from their murderous attacks. They were joined by Captain John Underhill and 20 or so men from Massachusetts. Before departing they likely observed a Day of Prayer and heard a sermon from Rev. Thomas Hooker.[9]

Before engaging the Pequots, they first sought help from friendly Indian tribes. The Mohicans, led by their chief Uncas, allied with them, sending 70 men to fight. They met with the Narragansetts, led by Canonicus and Miantonomoh. These chiefs supported them in the efforts against their common enemy but thought the whites were too weak to defeat the mighty Pequots, who had 2000 to 3000 warriors,[10] but nonetheless sent about 400 of their men to join them in battle. The colonists were glad for this support but had some concern of the fidelity of their Indian allies. Captain Underhill said one day he found Chaplain Stone praying with the soldiers, with these words:

“O Lord God, if it be thy blessed will, vouchsafe so much favor to thy poor distressed servants, as the manifest one pledge of thy love that may confirm us of the fidelity of these Indians toward us, that now pretend friendship and service to us, that our hearts may be encouraged the more in this work of thine.”[11]

Not long after this prayer, they heard that five Pequots were slain by the Mohicans. One historian records how “the news was welcome to them, and looked upon as a special providence.”[12]

As they marched through the wilderness seeking the Pequot fort, they asked for the chaplain’s advice in military strategy, which before giving he spent a night in prayer seeking wisdom from God. The captain acknowledged God’s leadership in directing them on their way. The day before the fight, a fast day was observed in Massachusetts.[13] On the eve of the battle, the chaplain earnestly prayed for the hungry and tired men. On the morning of the attack he “yielded themselves up to God and entreated his assistance.”[14] They needed His assistance for they were greatly outnumbered.

As they approached the stronghold of the Pequots, the allied Indians, who greatly feared the Pequot leader Sassacus, slunk back. So on May 26, 1637, only 77 Englishmen attacked the fort that the Pequots had built on the summit of a hill. “The colonists were fighting for the security of their homes; if defeated, the war-whoop would resound near their cottages, and their wives and children be abandoned to the scalping-knife and the tomahawk.”[15] While the English had superior weapons, the Pequots greatly outnumbered them, so during the initial stages of the battle the English decided to burn them out, casting firebrands on the cabins and fort. Everything quickly became inflamed and in the chaos, the English were able to take down the Pequots. About 600 Indians, mostly men but also some women and children, perished in the flames and in the battle.[16] The Pequots who escaped the fighting were caught and killed by the Indian allies who had remained at a distance. Only five got away.