By Stephen McDowell

In the 1980s The National Commission on Excellence in Education issued a report entitled “A Nation at Risk.’’ In that report they stated: “If an unfriendly foreign power had attempted to impose on America the mediocre educational performance that exists today, we might well have viewed it as an act of war.’’

Why are we a nation at risk today? One primary reason is due to the mediocre educational performance that exists today that results from the state monopoly of education where the anti-christian, man-centered religion of humanism is preached 5 days a week to 40-50 million of our youth, which is leading t hem and our nation into bondage.

hem and our nation into bondage.

This man-is-god religion (where man is the source of right and wrong and there are no absolutes) is also predominant in the market place of ideas—in the media, movies, television, and arts.

Johnny is in trouble today.

Johnny is in trouble—not because he is playing hooky from school, but because he is attending school.

Some of the most negative influences that young Americans can face today are found in public schools. In the past few decades this has exponentially worsened. In 1940 the top offenses in public schools were chewing gum, talking in class, unfinished homework, and running in the halls. In 1980 the top offenses were drugs, drunkenness, assault, murder and rape.

While at school, Johnny not only is confronted with drugs, immorality and violence, but he is also receiving a second rate education. From 1963-1980 Scholastic Aptitude Test scores dropped consistently each year (since 1980 they increased slightly for a few years and then began dropping again). The average verbal scores of the SAT dropped over 50 points and the average math scores dropped over 35 points.

As a result of decreasing literary skills, college textbooks are being rewritten at a lower grade level so that the students can understand them. Most newspapers and magazines are written at about a sixth grade level which is now the reading level of the average American. [To compare the literacy level of today with early America, read the Federalist Papers, which were written for farmers and other common citizens in New York. Today’s college graduates find them difficult.]

“But how can this be?’’ you may ask, “for Johnny is getting better grades than ever.’’ This is true, which makes the problem even worse, for many young people do not know how little they are learning.

Take for example, the young man who graduated as valedictorian from his Washington, D.C. high school yet was refused admission to George Washington University because his SAT scores were so low (320 on the verbal, which was the bottom 13% nationally of high school seniors; and 280 on the math, which was the bottom 2%). Due to his excellent grades he understandably considered himself a superior student, yet in the words of the dean of admissions of George Washington University, “He’s been deluded into thinking he’s gotten an education.’’

He, like many others in our public education system, has been conned. Grade inflation has only contributed to hiding the crisis that faces our public schools today.

Many Americans have been deluded into thinking they have gotten an education. They may not be functionally illiterate (though tens of millions are), but way too many are culturally and morally illiterate.

What is the problem?

Educational leaders acknowledge that there are problems with our public schools. Most of their suggested solutions involve spending more money (or in centralizing education). In the past few decades, however, the public education system has dramatically increased its expenditures—in 1950 $8.8 billion was spent on education in America; in 1985, $261 billion; in 1990, $353 billion; and in 1992, $445 billion. Elementary and high schools spent $274 billion in 1992-93. After adjusting for inflation, spending was up 40% in the 10 years since 1982-1983. Well over $5000 per student per year is spent (on the average) in secondary public education. [Washington D.C. schools spend almost $10,000 per child, but is near the bottom of all cities nationally in academics.] Yet with all this spending, the educational skills of our students have decreased.

Lack of money is not the problem in our public schools. The problems have not been due to a lack of financial resources, but of spiritual resources. The problem is with the philosophy that forms the foundation of education in America. Colossians 2:8 is very insightful in this matter:

“See to it that no one takes you captive through philosophy and empty deception, according to the tradition of men, according to the elementary principles of the world, rather than according to Christ.’’

There are two basic philosophies — that which is according to the world, and that which is according to Christ. A worldly or humanistic (man-centered) philosophy always brings captivity or bondage, while a Christian philosophy brings liberty.

A worldly educational philosophy has controlled our public schools for some time. The result is bondage. For example, there are at least 40 million American adults who are functionally illiterate—they cannot read a want ad, a job application form, a label on a medicine bottle, or a safety sign at a work place. That is bondage! A vast majority of these people went to school enough to supposedly learn how to read. A more recent study has shown that 90 million American adults are unable to function in society due to lack of basic educational skills.

It has been said that the philosophy of education in one generation will be the philosophy of government in the next. The direction our nation has been going in recent decades is a result of the training those governing America have received in the schools in the past. Noah Webster knew the importance of educating youth.

Webster has been called the father of American scholarship and education. He affected the course of education in early America more than any other person. His blue-backed speller sold over 100 million copies from 1783 through the 1800s, and was designed to allow individuals to be self-taught. Webster spent over 26 years working on his dictionary, the first exhaustive dictionary of the English language. He was the first person to do extensive etymological research, mastering 28 languages during this study and writing of the dictionary. Besides his speller, he wrote a grammar, a reader, a U.S. History, and other textbooks. He translated his own version of the Bible, helped to start a college, started the first magazine in America, and started a newspaper. He was one of the first persons to publicly promote a constitutional convention in the 1780s. He secured copyright legislation on the state and national levels, served in civil government in many capacities, and wrote on a wide variety of topics. During his astoundingly productive life he also lovingly raised seven children. We would do well to listen to him.

Noah Webster wrote in the March, 1788, American Magazine: “the education of youth [is] an employment of more consequence than making laws and preaching the gospel, because it lays the foundation on which both law and gospel rest for success.’’

Is this true or heresy? It depends upon how you define education. It is certainly not true based upon modern views of education. Webster’s New World Dictionary of the American Language defines education as:

“1. the process of educating especially by formal schooling; teaching; training. 2. knowledge, ability, etc. thus developed. 3. a) formal schooling. b) a kind or stage of this: as, a medical education. 4. systematic study of the methods and theories of teaching and learning.’’

However, if we looked at how Webster defined education in his original dictionary published in 1828, we would readily agree with his statement. In this dictionary, Webster defined words biblically and generously used scriptural references. [Webster wouldn’t recognize the dictionary that bears his name today.] His definition was:

“Education – The bringing up, as a child; instruction; formation of manners. Education comprehends all that series of instruction and discipline which is intended to enlighten the understanding, correct the temper, and form the manners and habits of youth, and fit them for usefulness in their future stations. To give children a good education in manners, arts and science, is important; to give them a religious education is indispensable; and an immense responsibility rests on parents and guardians who neglect these duties.’’1

To Webster, the central goal of education was to train youth in the precepts of Christianity. He stated, “In my view, the Christian religion is the most important and one of the first things in which all children, under a free government, ought to be instructed…. No truth is more evident to my mind than that the Christian religion must be the basis of any government intended to secure the rights and privileges of a free people.’’2

We can see why such education lays the foundation for the success of the Gospel and the making of good laws, for only a people of good character and ideas can preserve religious and civil liberty. It was such a people that gave birth to liberty throughout the world. In Webster’s United States History book, he has a chapter on the U.S. Constitution. In there is a section with the heading, Origin of Civil Liberty, which contains this:

“ Almost all the civil liberty now enjoyed in the world owes its origin to the principles of the Christian religion… The religion which has introduced civil liberty, is the religion of Christ and his apostles, which enjoins humility, piety, and benevolence; which acknowledges in every person a brother, or a sister, and a citizen with equal rights. This is genuine Christianity, and to this we owe our free constitutions of government…’’ 3

How we educate the next generation will determine how our nation is governed in the next generation. This is why education of youth is of utmost importance.

From a Nation at Risk to a Nation on the Rise

The answer to our being a nation at risk is having a new generation of well trained and educated youth and adults – those who are knowledgeable of the truth and know how to think biblically. True knowledge (or knowledge of the truth) brings liberty, while ignorance produces bondage.

William Penn wrote in the Preface to The Frame of Government of Pennsylvania (1682):

“That… which makes a good constitution, must keep it, viz: men of wisdom and virtue, qualities, that because they descend not with worldly inheritances, must be carefully propagated by a virtuous education of youth.’’4

The father of the American Revolution, Samuel Adams, wrote in a letter October 4, 1790 to John Adams, then vice-president of the United States:

“Let divines and philosophers, statesmen and patriots, unite their endeavors to renovate the age, by impressing the minds of men with the importance of educating their little boys and girls, of inculcating in the minds of youth the fear and love of the Deity and universal philanthropy, and, in subordination to these great principles, the love of their country; of instructing them in the art of self-government, without which they never can act a wise part in the government of societies, great or small; in short, of leading them in the study and practice of the exalted virtues of the Christian system.’’5

Benjamin Franklin said: “A nation of well informed men who have been taught to know and prize the rights which God has given them cannot be enslaved. It is in the region of ignorance that tyranny begins.’’

Therefore, to go from a nation at risk to a nation on the rise, we need knowledgeable, well trained and educated youth. This requires parents and teachers who understand the importance of educating youth and who are willing to assume the responsibility and pay the price necessary to produce a new generation of Americans. The cost will involve time, effort, and money (though it doesn’t necessarily require much money).

Those who have sought to do this not only hold the future of the children in their hands, but the future of our nation. As parents have given up their responsibility to educate their children, the state has assumed it. The state has failed to educate properly. The solution is for parents to take back that which belongs to them.

According to the Bible it is primarily the responsibility of fathers and mothers to educate their children. Ephesians 6:1-4 says that fathers are to bring up their children in the nurture and admonition of the Lord. The Greek word for nurture means to tutor, to personally have input into a child. Fathers should personally be involved in training and educating their children.

God has put within mothers the natural vocation to teach. Proverbs 1:8 says: “Listen, my son, to your father’s instruction and do not forsake your mother’s teaching’’ (NIV).

Daniel Webster spoke of the eternal impact of mothers: “…the mothers of a civilized nation…[work], not on frail and perishable matter, but on the immortal mind, moulding and fashioning beings who are to exist for ever…. They work, not upon the canvas that shall perish, or the marble that shall crumble into dust, but upon mind, upon spirit, which is to last for ever, and which is to bear, for good or evil, throughout its duration, the impress of a mother’s …hand.’’6

Mothers in early America understood and fulfilled their primary mission. This is summarized by the inscription on The Pilgrim Mother statue in Plymouth, Massachusetts: “They brought up their families in sturdy virtue and a living faith in God without which nations perish.’’

Parents have the right and the responsibility to govern the education of their children. They can delegate aspects of it to others, but they are still responsible. This was certainly the philosophy of colonial Americans.

Churches and the private sector have a role in education as well. They can establish schools which will allow parents to supplement their children’s education and which will be a means of providing for the indigent in the community.

Education in Early America

Education in early America was much different than that of today, in form and results. Most education was done by the home or church. This is where the ideas and character were implanted in our founders. Such training produced one of the greatest group of men—in thought and character—of all time.

Samuel Blumenfeld says: “Of the 117 men who signed the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation and the Constitution, one out of three had had only a few months of formal schooling, and only one in four had gone to college. They were educated by parents, church schools, tutors, academies, apprenticeship, and by themselves.’’7

They were a product of a system of education much different than today.

What was education in early America like?

1. Education was centered in the home.

Almost every child in America was educated. At the time of the Revolution, the literacy level was virtually 100% (even on the frontier it was greater than 70%). John Adams said to find someone who couldn’t read was as rare as a comet. The colonists had a Christian philosophy of education—they felt everyone should be educated, because everyone needed to know the truth for themselves.

Tutors were at times hired to supplement education. Ministers were most often the tutors. Many of the founders of America had ministers as tutors including Jefferson, Madison, and Noah Webster. Those that went to colleges would have been instructed by ministers.

2. First schools were started by the church.

The first school in New England was the Boston Latin School. It was started in 1636 by Rev. John Cotton to provide education for those who were not able to receive it at home.

For centuries, most schools were Church schools, started by the major Christian sects. Some of these schools charged moderate tuition fees, but generally taught the children of the poor for free.

3. First common (public) schools were thoroughly Christian.

Massachusetts Education Laws:

In 1642 the General Court enacted legislation requiring each town to see that children were taught, especially “to read and understand the principles of religion and the capital laws of this country…’’8

The “Old Deluder Satan’’ Act of 1647 stated: “It being one chief project of that old deluder, Satan, to keep men from the knowledge of the Scriptures…’’ The General Court went on to order any town with 50 families to hire a teacher, and those that increased to 100 families to set up a school to prepare youth for the university. 9

Grammar School at Dorchester, MA: Rules adopted by town meeting in 1645 required the schoolmaster “to commend his scholars and his labors amongst them unto God by prayer morning and evening, taking care that his scholars do reverently attend during the same.’’ The schoolmaster examined each student at noon on Monday to see what he had learned from the Sabbath sermon. On Friday afternoon at 2:00, he was to catechize them “in the principles of Christian religion.’’10

As time went on private schools flourished more than common schools (especially as the Puritan influence in common schools decreased). The Christian community saw the private schools were more reliable. “By 1720 Boston had far more private schools than public ones, and by the close of the American Revolution many towns had no common schools… at all.’’11

Most of the schools in the Middle and Southern Colonies were church schools. Public schools in the Middle Colonies were found only in the cities, and they were still in a minority. There were no public schools in the Southern colonies until 1730 and only five by 1776. Remember, the colonies has a literacy level (both quantity and quality) equal to or greater than that of today with our tens of thousands of schools and hundreds of billions of dollars supporting state education.

4. Character of teachers

To reveal the character of the teachers in early America many examples could be given, from Ezekiel Cheever (1614-1708) a schoolmaster for 70 years in New England, to Noah Webster, Emma Willard, and many ministers. We will briefly examine one, Nathan Hale.

Hale taught school in East Haddam, Connecticut after he graduated from Yale College in the fall of 1773 at age 18. After 4 or 5 months at this country schoolhouse, he accepted the position of mastership of a private school in New London. He wrote to friends: “I love my employment.’’ In July, 1775 he resigned to accept a commission in the Colonial Army.

During the early years of the Revolutionary War, information of the position and strength of the British troops was vitally needed by the American forces. Someone was needed to disguise themselves and travel behind the enemy lines to attempt to obtain this data. Captain Nathan Hale volunteered for this hazardous service because he saw it as an opportunity to serve his country and further the cause of liberty.

Disguised as a civilian, Hale passed into Long Island and observed the position, strength, and movement of the British army. As he was attempting to return, he was captured, carried before Sir William Howe, where he confessed his rank in the American army and his purpose, which the papers he was carrying confirmed. Orders were immediately given for Hale to be executed the next morning as a spy.

One historian writes: “The order was accordingly executed in a most unfeeling manner, and by as great a savage as ever disgraced humanity. A clergyman, whose attendance he desired, was refused him; a bible for a moment’s devotion was not procured, though he requested it. Letters, which on the morning of his execution, he wrote to his mother, and other friends, were destroyed; and this very extraordinary reason given by the provost marshal, `that the rebels should not know that they had a man in their army, who could die with so much firmness.’ ‘’12

Unknown to those around him, and without a single friend to offer him the least consolation, Hale ascended the gallows on the morning of September 22, 1776, offering these words as his dying observation: “I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country.’’13

This courageous young man saw the value of liberty, and was motivated by its light. “Neither expectation of promotion nor pecuniary reward, induced him to this attempt. A sense of duty, a hope that he might in this way be useful to his country, and an opinion which he had adopted, that every kind of service necessary to the public good, became honourable by being necessary, were the great motives which induced him to engage in an enterprize, by which his connexions lost a most amiable friend, and his country one of its most promising supporters.’’14

This is the type of character teachers in early America possessed. This same type of character is needed by teachers today. Teachers today may not have to physically give up their life for the cause of liberty, but they should inspire those they teach to see the necessity of doing all they can to preserve our God given liberty and rights.

5. Apprenticeship or college

Up until age 8, almost all colonial youth were taught at home. At around this age, some had tutors to supplement their education and some attended schools. At around age 13-15, the young men would be apprenticed at some trade (often at home) or some few would attend college.

6. Colleges and Universities

106 of the first 108 colleges were started on the Christian faith. By the close of 1860 there were 246 colleges in America. Seventeen of these were state institutions; almost every other one was founded by Christian denominations or by individuals who avowed a religious purpose.15 Many of the state colleges were Christian as well.

Harvard College, 1636

The following report on Harvard College, from “New Englands First Fruits’’ published in 1643, reveals the purpose for it’s establishment:

“After God had carried us safe to New England, and wee had builded our houses, provided necessaries for our liveli-hood, rear’d convenient places for Gods worship, and settled the Civil Government: One of the next things we longed for, and looked after was to advance Learning, and perpetuate it to Posterity, dreading to leave an illiterate Ministry to the Churches, when our present Ministers shall lie in the Dust.’’16

An Original Rule of Harvard College:

“Let every Student be plainly instructed, and earnestly pressed to consider well, the maine end of his life and studies is, to know God and Jesus Christ which is eternall life, (John 17:3), and therefore to lay Christ in the bottome, as the only foundation of all sound knowledge and Learning.’’17

William and Mary, 1691

The College of William and Mary was started mainly due to the efforts of Rev. James Blair in order, according to its charter of 1691, “that the Church of Virginia may be furnished with a seminary of ministers of the Gospel, and that the youth may be piously educated in good letters and manners, and that the Christian religion may be propagated among the Western Indians to the glory of Almighty God.’’18

Yale University, 1701

Yale University was started by Congregational ministers in 1701, “for the liberal and religious education of suitable youth… to propagate in this wilderness, the blessed reformed Protestant religion…’’19

Princeton, 1746

Associated with the Great Awakening, Princeton was founded by the Presbyterians in 1746. Rev. Jonathan Dickinson became its first president, declaring, “cursed be all that learning that is contrary to the cross of Christ’’20 To help raise funds for the college in England, a General Account was prepared that stated “the two principal Objects the Trustees had in View, were Science and Religion. Their first Concern was to cultivate the Minds of the Pupils, in all those Branches of Erudition, which are generally taught in the Universities abroad; and to perfect their Design, their next Care was to rectify the Heart, by inculcating the great Precepts of Christianity, in order to make them good Men’’21 .

University of Pennsylvania, 1751

Ben Franklin had much to do with the beginning of the University of Pennsylvania. It was not started by a denomination, but its laws reflect its Christian character. Consider the first two Laws, relating to the Moral Conduct, and Orderly Behaviour, of the Students and Scholars of the University of Pennsylvania (from 1801):

“1. None of the students or scholars, belonging to this seminary, shall make use of any indecent or immoral language: whether it consist in immodest expressions; in cursing and swearing; or in exclamations which introduce the name of GOD, without reverence, and without necessity.

“2. None of them shall, without a good and sufficient reason, be absent from school, or late in his attendance; more particularly at the time of prayers, and of the reading of the Holy Scriptures.’’22

Columbia, 1754

In 1754, Samuel Johnson became the first president of Columbia (called King’s College up until 1784). In that year he composed an advertisement announcing the opening of the college. It stated:

“The chief Thing that is aimed at in this College is, to teach and engage the Children to know God in Jesus Christ, and to love and serve him, in all Sobriety, Godliness and Righteousness of Life, with a perfect Heart, and a willing Mind; and to train them up in all virtuous Habits, and all such useful Knowledge as may render them creditable to their Families and Friends…’’23

Dartmouth, 1770

Congregational pastor Eleazar Wheelock (1711-79) secured a charter from the governor of New Hampshire in March, 1770, to establish a college to train young men for missionary service among the Indians. The college was named after Lord Dartmouth of England who assisted in raising funds for its establishment. Its Latin motto means: “the voice of one crying in the wilderness.’’ The first students met in a log cabin and when weather permitted Dr. Wheelock held morning and evening prayers in the open air.24

Some other colleges started before America’s Independence include: Brown, started by the Baptists in 1764; Rutgers, 1766, by the Dutch Reformed Church; Washington and Lee, 1749; and Hampden-Sidney, 1776, by the Presbyterians.

7. Textbooks

The Bible and its principles were the focal point of education. In 1690, John Locke said that children learned to read by following “the ordinary road of Hornbook, Primer, Psalter, Testament and Bible.’’25

The New Haven Code of 1655 required that children be made “able duly to read the Scriptures… and in some competent measure to understand the main grounds and principles of Christian Religion necessary to salvation.’’26

a. The Bible was the central text.

John Adams reflected the view of the founders in regard to the place of the Bible in society when he wrote:

“Suppose a nation in some distant Region, should take the Bible for their only law-book, and every member should regulate his conduct by the precepts there exhibited!… What a Utopia; what a Paradise would this region be!’’ John Adams, Feb. 22, 1756. 27

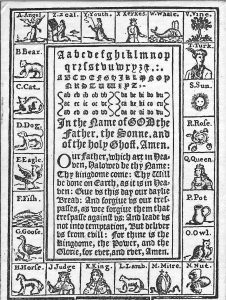

b. Hornbooks

Hornbooks had been used to teach children to read from as far back as 1400 in Europe. They came to America with the colonists and were common from the 1500s – 1700s. A hornbook was a flat piece of wood with a handle, upon which a sheet of printed paper was attached and covered with transparent animal horn to protect it. A typical hornbook had the alphabet, the vowels, a list of syllables, the invocation of the Trinity, and the Lord’s Prayer. Some had a pictured alphabet.

c. Catechisms

Catechisms were used extensively in early education in America. There were over 500 different catechisms according to Increase Mather. The most widely used catechism was one which the Puritans brought with them from England, The Foundation of Christian Religion gathered into sixe Principles, by William Perkins. Later, the Westminster Catechism became the most prominent one.

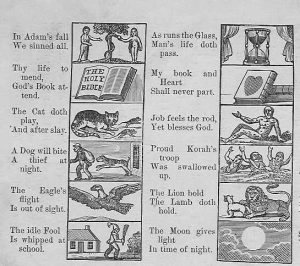

d. The New England Primer

Another important educational book was the New England Primer, which was first published in Boston around 1690 by devote Protestant Benjamin Harris. It was the most prominent schoolbook for about 100 years, and was frequently reprinted through the 1800s. It sold over 3 million copies in 150 years. The rhyming alphabet is its most characteristic feature.

From a 1777 Primer, the alphabet was taught with this rhyme:

A In Adam’s Fall

We sinned all.

B Heaven to find

The Bible Mind.

C Christ crucify’d

For sinners dy’d.

D The Deluge drown’d

The Earth around.

E Elijah hid

By Ravens fed.

F The judgment made

Felix afraid.

G As runs the Glass,

Our Life doth pass

H My Book and Heart

Must never part. . . .

It is easy to see its Christian character. The Primer underwent various modifications over the years.

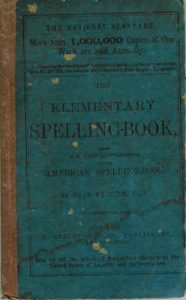

e. Webster’s Blue-Backed Speller

Webster’s speller was first published in 1783 and sold over 100 million copies during the next century. It was the most influential textbook of the era and was written to instill into the minds of the youth “the first rudiments of the language and some just ideas of religion, morals, and domestic economy.’’ Its premise was that “God’s word, contained in the Bible, has furnished all necessary rules to direct our conduct.’’ It included a moral catechism, large portions of the Sermon on the Mount, a paraphrase of the Genesis account of creation, and numerous moral stories.

f. The McGuffey Readers

Written by minister and university professor William Holmes McGuffey, the McGuffey Readers “represent the most significant force in the framing of our national morals and tastes’’ other than the Bible.28 First published in 1836, they sold over 122 million copies in 75 years and are still used today in some schools. McGuffey wrote in the Preface to the Fourth Reader:

“From no source has the author drawn more copiously, in his selections, than from the sacred Scriptures. For this, he certainly apprehends no censure. In a Christian country, that man is to be pitied, who at this day, can honestly object to imbuing the minds of youth with the language and spirit of the Word of God.’’29

While there were many other textbooks (especially in the 1800s), the ones just mentioned were some of the most important.

Education in Religion was central to our Founders

We have already given quotes of Noah Webster, Samuel Adams, John Adams, Franklin, Penn, and Daniel Webster, and could talk quite sometime of the Biblical view America’s founders had of education. We will look at only a few more comments.

Benjamin Rush was a signer of the Declaration of Independence; a professor of medicine, making many contributions in that field in practice and writing; a leader in societies for the abolition of slavery; president of various Bible and medical societies; a principal founder of Dickenson College; and a leader in education. Concerning education he wrote:

“I proceed, in the next place, to enquire what mode of education we shall adopt so as to secure to the state all the advantages that are to be derived from the proper instruction of youth; and here I beg leave to remark that the only foundation for a useful education in a republic is to be laid in religion. Without this, there can be no virtue, and without virtue there can be no liberty, and liberty is the object and life of all republican governments.’’30

Gouverneur Morris, a signer of the Constitution, wrote: “Religion is the only solid basis of good morals; therefore, education should teach the precepts of religion, and the duties of man towards God.’’31

Fisher Ames said “the Bible [should] retain the place it once held as a school book. Its morals are pure, its examples captivating and noble. The reverence for the sacred book that is thus early impressed lasts long; and probably, if not impressed in infancy, never takes firm hold of the mind.’’32

Northwest Ordinance, 1787 (1789): “Religion, morality and knowledge, being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools and the means of education shall forever be encouraged.’’

The type of education that shaped our Founders character and ideas was thoroughly Christian. It imparted Christian character and produced honest, industrious, compassionate, respectful, and law-abiding men. It also imparted a Biblical world-view and produced people who were principled thinkers.

This was reflected in the constitutions and laws of our states and nation. America was established as the first constitutional federal republic in history. Christian principles of self-government, union, virtue, the value of the individual, and recognition of God-given inalienable rights to life, liberty and property are incorporated in our nation’s fabric. Christian economic principles of individual enterprise, private property rights, and the free market formed the foundation of our prosperity as a nation.

In early America, the people made the laws and the churches made the people. Their ideas and character were shaped by Christianity.

Example of George Washington

What type of men were produced by the biblical education of colonial America? A brief look at George Washington will help answer that.

Most Americans are familiar with some aspects of Washington’s life and the important role he played in the history of America. One historian said he was the American Revolution, due to his overwhelming influence in winning the war. He played a vital role in forming the Constitution and as our first President he started our nation on the right path. He certainly was a man of Christian character.

One historian said he was “unquestionably the greatest man that the world has produced in the last one thousand years.’’

How was Washington trained and educated? By his father, mother, and brother primarily. Only very briefly did he attend a nearby school and he never went to college.

His strength was his character. Following is an incident that reveals this:

Washington endeavored “to impress upon the soldiers under his command a profound reverence for the name and the majesty of God, and repeatedly, in his public orders during the Revolution, the inexcusable offense of profaness was rebuked.’’

“On a certain occasion he had invited a number of officers to dine with him. While at table one of them uttered an oath. General Washington dropped his knife and fork in a moment, and in his deep undertone, and characteristic dignity and deliberation, said, `I thought that we all supposed ourselves gentlemen.’ He then resumed his knife and fork and went on as before. The remark struck like an electric shock, and, as was intended, did execution, as his observations in such cases were apt to do. No person swore at the table after that. When dinner was over, the officer referred to said to a companion that if the General had given him a blow over the head with his sword, he could have borne it, but that the home thrust which he received was too much—it was too much for a gentleman!’’33

Washington was not very loud or talkative but he was very commanding in his words and presence. Historian E.L. Magoon said that Washington emanated a presence about him like no other person; and his words certainly carried a great force. It has been said that the value and force of words depends upon who stands behind them; that is, upon the character of him who utters them. Washington’s character, instilled in him through a godly education, was the source of his strength and greatness.

America today is crying out for leaders—men of character and full of truth. We need to go from a nation at risk to a nation on the rise. We need to bring Godly reform. To accomplish this, we must have a revolution. Thankfully, a revolution is occurring, for millions of parents are assuming their responsibility to govern the education of their children, whether in church schools, or in private schools, or at home. This should produce in us hope for our future.

In summary, what can we do? It is not enough to simply restore prayer to public schools. This will not lead us out of bondage. For the present public educational system is the “Philistine cart’’ (1 Chron. 13) that produced the bondage in the first place. It is not God’s method for training the future generations, but it is the world’s (or man’s) method. It needs to be completely dismantled. Here’s what we can do:

1. Parents must assume the responsibility to govern the education of their children. They must participate, even if they send them to school.

2. Churches and private schools can provide support for parents and education for those who are not receiving it at home.

3. Businesses can be involved via apprenticeship programs.

4. Everyone can work to restore a Christian philosophy and methodology to education in America.

5. New Christian colleges can be started.

6. We should work to privatize public education.

These are a few steps we can take to lead our nation out of bondage into liberty – out of Egypt and into the promised land.

I encourage you parents to continue to work on that imperishable canvas of your child’s heart and mind, and to you teachers, upon those that have been entrusted to your care. The destiny of our nation is at stake!

* * * * * * *

END NOTES

1. An American Dictionary of the English Language, Noah Webster, originally published in 1828. Reprint by the Foundation for American Christian Education, 1980.

2. Letter to David McClure, October 25, 1836. Letters of Noah Webster, Harry R. Warfel, editor, New York: Library Publishers, 1953, p. 453.

3. Noah Webster, History of the United States, New Haven: Durrie & Peck, 1833, pp. 273-274.

4. Sources of Our Liberties, edited by Richard L. Perry, Chicago: American Bar Foundation, 1978, p. 211.

5. The Life and Public Services of Samuel Adams, by William V. Wells, Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1865, Vol. 3, p. 301.

6. The Works of Daniel Webster, Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1854. Vol. 2, p. 107.

7. Samuel Blumenfeld, NEA–Trojan Horse in American Education.

8. Richard Morris, editor, Significant Documents in United States History, Vol. 1, New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Co., 1969, p. 19.

9. Ibid., p. 20.

10. The Pageant of America, Ralph Henry Gabriel, editor, New Haven: Yale University Press, Vol. 10, 1928, p. 258.

11. Blumenfeld.

12. Jedidiah Morse, Annals of the American Revolution, first published 1824, reissued 1968 by Kennikat Press, p. 260.

13. George Bancroft, History of the United States of America, Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1879, Vol. 5, p. 408.

14. Morse, p. 260.

15. The Pageant of America, p. 315.

16. Ibid., p. 256.

17. Mark Beliles and Stephen McDowell, America’s Providential History, Charlottesville: Providence Foundation, 1989, p. 110.

18. Francis Simkins et al, Virginia: History, Government, Geography, New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1964, pp. 48-49.

19. B.F. Morris, Christian Life and Character of the Civil Institutions of the United States of America, Philadelphia: George W. Childs, 1864, p. 239.

20. Daniel Dorchester, Christianity in the United States, New York: Hunt & Eaton, 1895, p. 244.

21. The Pageant of America, p. 306.

22. Ibid., p. 307.

23. Ibid., p. 309.

24. Ibid., p. 312.

25. Ibid., p. 258.

26. Ibid.

27. The Earliest Diary of John Adams, ed. L.H. Butterfield. Cambridge, MA: the Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1966, 1:9.

28. Beliles and McDowell, p. 108.

29. William McGuffey, The Eclectic Fourth Reader, originally printed in 1838, republished by Mott Media, 1982, p. x.

30. Benjamin Rush, Thoughts Upon the Mode of Education Proper in a Republic, Early American Imprints, 1786.

31. The Life of Governeur Morris by Jared Sparks, 1832, Vol. 3, p. 483.

32. Works of Fisher Ames, originally published in 1854, reprinted by Liberty Classics, 1983. Vol. 1, p. 12.

33. William Johnson, George Washington the Christian. Reprinted by Mott Media, Milford, MI, 1976.

orance produces bondage: “A nation of well informed men who have been taught to know and prize the rights which God has given them cannot be enslaved. It is in the region of ignorance that tyranny begins.”

orance produces bondage: “A nation of well informed men who have been taught to know and prize the rights which God has given them cannot be enslaved. It is in the region of ignorance that tyranny begins.” ent — in the earth. Children are arrows or weapons that God gives the family to prepare to shoot into the culture and the future (Psalm 127:4). If the family is faulty, the fulfillment of the mission wanes and the nation will decline.

ent — in the earth. Children are arrows or weapons that God gives the family to prepare to shoot into the culture and the future (Psalm 127:4). If the family is faulty, the fulfillment of the mission wanes and the nation will decline. es and the nation will decline.

es and the nation will decline.

hem and our nation into bondage.

hem and our nation into bondage.