Home

WELCOME TO PROVIDENCE FOUNDATION

Transforming Culture

for Christ: Training

Leaders, Discipling

Nations.

The Providence Foundation is a Christian educational organization whose mission is to train and network leaders to transform their culture for Christ, and to teach all citizens how to disciple nations.

Shop Our Books

-

Sale!

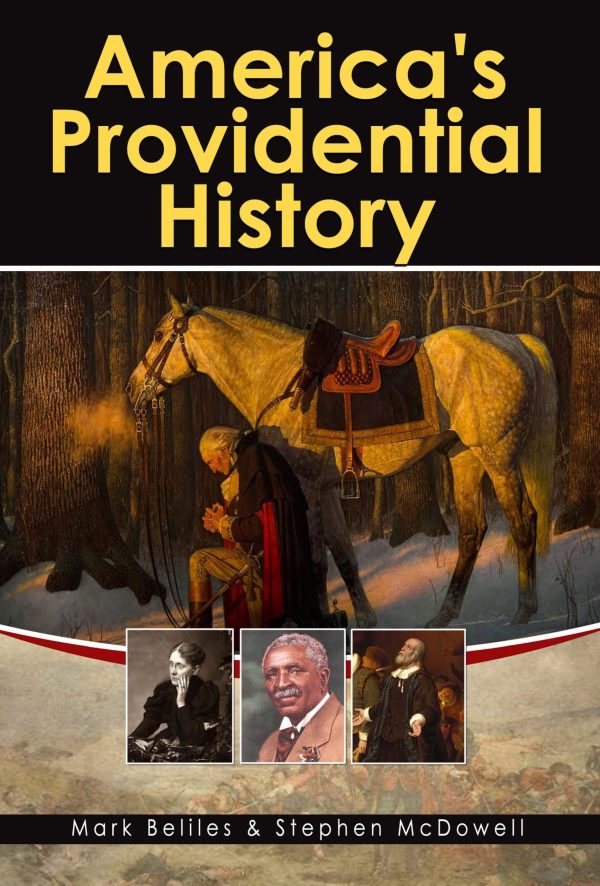

America’s Providential History (Revised and Expanded)

Original price was: $24.95.$21.95Current price is: $21.95. Add to cart Buy Now -

Educated for Liberty

$10.00 Add to cart Buy Now -

Sale!

How the Bible Educated America to Live in Liberty

Original price was: $8.95.$6.95Current price is: $6.95. Add to cart Buy Now -

Sale!

Ruling Over the Earth: A Biblical View of Civil Government

Original price was: $19.95.$17.95Current price is: $17.95. Add to cart Buy Now -

Sale!

Stewarding the Earth, A Biblical View of Economics

Original price was: $21.95.$19.95Current price is: $19.95. Add to cart Buy Now -

The Bible: America’s Source of Law and Liberty

$15.95 Add to cart Buy Now

Podcast

America’s Providential History

with Stephen McDowell

God watches over His creation and directs the course of mankind to fulfill His purposes. Any view of history that denies His Providence is not true history at all. This weekly podcast presents the real story of America by exploring the hand of God in our history.

Film

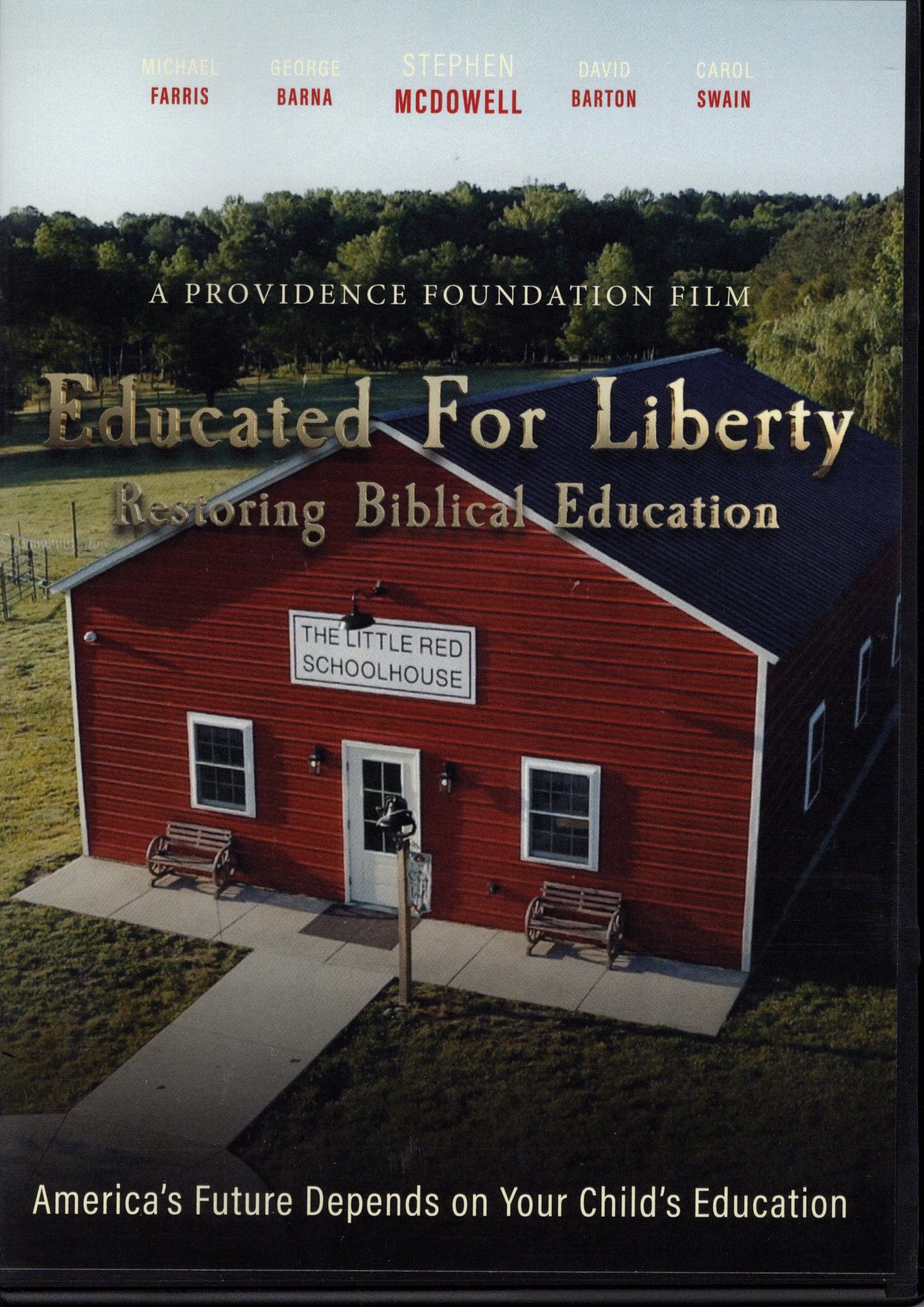

Educated for Liberty

Restoring Biblical Education

Educated for Liberty explores how home-centered biblical education produced the free and flourishing nation of America, while secular education has led to great moral and academic decline. Restoring biblical education is the solution to our loss of liberty and excellence.

PF UNIVERSITY

Be Empowered by Our Courses

The courses offered by the Providence Foundation Biblical Worldview University (BWU) are designed to equip leaders of education, business, and politics to transform their culture for Christ, and to train all citizens how to disciple nations.

DONATE

Advance Providence Foundation

Support Providence Foundation today! Choose Minuteman, Patriot, or Founder level and make a monthly impact. Or select ‘Custom’ to contribute now. Join us in shaping our nation’s future

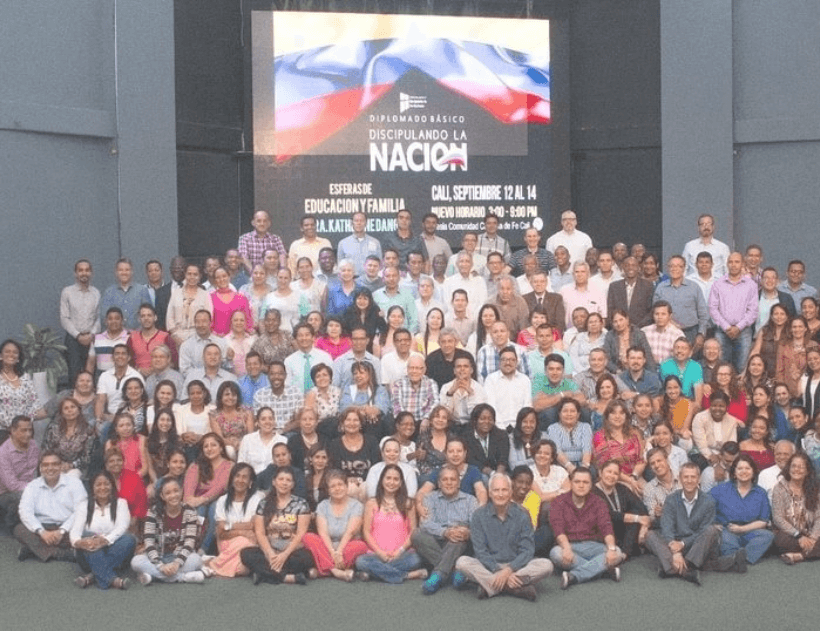

An Urgent Call for Biblical Renewal in the Nations

Jesus’ call to disciple nations, echoed by Matthew Henry, emphasizes integrating biblical values into society. Personal revival sparks individual change, while historical revivals transform communities. Neglect risks societal decline. God’s mandate spans governance, education, media, politics, business, family, and church, requiring equipping individuals with biblical wisdom to spread a biblical worldview.

VIDEOS