PF UNIVERSITY

By Stephen McDowell

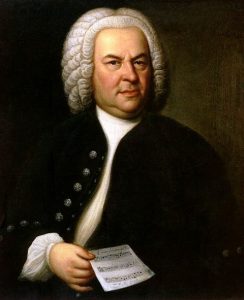

Johann Sebastian Bach is arguably the greatest composer that ever lived. He transformed music. One of his works, The Art of Fugue, has been called “one of the loftiest accomplishments of the human mind.”[1] According to one biographer, his Summa, or summation, works “approach musical perfection, and rival any intellectual accomplishment in the history of man.”[2]

His deep Christian faith is evident in his music and words. He wrote: “The aim and final end of all music should be none other than the glory of God and th e refreshment of the soul.”[3] Most of Bach’s work was aimed at transforming worship – his ultimate goal was “a well-regulated church music, to the Glory of God.”[4] His hundreds of cantatas were musical sermons. His five Passions tell of the work of Christ. He produced hundreds of sacred works for organ and hundreds more works to directly glorify God. He began the manuscript scores of his sacred compositions with the letters J.J., which is the abbreviation for Jesu, Juva or “Jesus, help.” He concluded these scores with S.D.G., which is Soli Deo Gloria, “to God alone the glory.”[5]

e refreshment of the soul.”[3] Most of Bach’s work was aimed at transforming worship – his ultimate goal was “a well-regulated church music, to the Glory of God.”[4] His hundreds of cantatas were musical sermons. His five Passions tell of the work of Christ. He produced hundreds of sacred works for organ and hundreds more works to directly glorify God. He began the manuscript scores of his sacred compositions with the letters J.J., which is the abbreviation for Jesu, Juva or “Jesus, help.” He concluded these scores with S.D.G., which is Soli Deo Gloria, “to God alone the glory.”[5]

His “secular” compositions were also written for the glory of God. He started a volume of instructional pieces written for his son with the letters, “I.N.J.,” which indicates In Nomine Jesu or “in the name of Jesus.”[6] This Christian aspect of Bach’s work is generally ignored by modern academia.

God is glorified both in the words Bach used to tell a story, but also in the music itself. Bach has mined from the depth of God’s creation the laws of music that the Creator hid for us to discover that would lift up mankind and glorify the Lord. Even fallen men can sense this when they hear and study Bach’s work. As a child taking piano lessons I always enjoyed Bach. I knew nothing of his faith, nor little of how Bach technically transformed music, but I sensed the greatness in what I heard and was learning to play. Had I been given the words and learned of his motives, I might have encountered the living God much sooner than I did. Nonetheless, as Bach knew, you can find God in Biblical music, just as you can see Him in His creation (Romans 1:20). For Bach, “theological and musical scholarship were two sides of the same coin: the search for divine revelation, or the quest for God.”[7]

After Bach’s death in 1750 his work was almost forgotten primarily due to growing enlightenment thought in Europe which rejected his thoroughly Christian music. Two generations later, the famous Lutheran composer and performer Felix Mendelssohn (1809-47) took it upon himself to revive Bach’s legacy. When he was ten years old, Mendelssohn’s mother gave him a score of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion. Later he decided to present a performance for the public. Chorus rehearsals lasted nearly two years since “no one had sung music of this magnitude or complexity since the death of Bach.”[8]

At the age of 20, on March 11, 1829, Mendelssohn conducted the Passion. It was described as being “like the opening of the gate of a long-closed temple.”[9] Thousands flocked to hear repeat performances in many cities. Mendelssohn’s sister later described the concert hall as having “all the air of a church … the most solemn devotion pervaded the whole…. Never have I felt a holier solemnity vested in a congregation than on that evening.”[10]

Mendelssohn was successful in reviving the memory of and interest in Bach. It remains to this day; however, what has been forgotten is Bach’s central motive of glorifying God and pointing people toward Him. Mendelssohn wrote of one of Bach’s chorales that “the melody seemed interlaced with garlands of gold, evoking in me the thought: were life deprived of all trust, all faith, this chorale would restore it to me.”[11]

To get a taste of Bach’s genius and Biblical motives, I invite you to listen to the opening of the St. Matthew Passion, and as you do consider how Leonard Bernstein, the influential American composer and conductor, describes what is occurring:

The orchestral introduction … sets the mood of suffering and pain, preparing for the entrance of the chorus which will sing the agonized sorrow of the faithful at the moment of crucifixion. And all this is done in imitation, in canon. “Come, ye Daughters, share my anguish,” sing the basses, and they are [imitated] by the tenors [while] the female voices are singing a counter-canon of their own. The resulting richness of all the parts, with the orchestra throbbing beneath, is incomparable.

Then suddenly the chorus breaks into two antiphonal choruses. “See Him!” cries the first one. “Whom?” asks the second. And the first answers: “The Bridegroom see. See Him!” “How?” “So like a Lamb.” And then over against all this questioning and answering and throbbing, the voice of a boys’ choir sing out the chorale tune, “O Lamb of God Most Holy,” piercing through the worldly pain with the icy-clear truth of redemption.[12]

For best effect, you should listen to this piece at least four or five times since, according to prominent composer Robert Schumann, “Bach seems to grow more profound the oftener heard.”

To taste “one of the loftiest accomplishments of the human mind,” listen to The Art of Fugue.

Bach continues to teach us today through his music, and he will do so for all of time since he discovered how to glorify God in his unsurpassed and innovative work. Music historian Edward Dickinson wrote: “There is no loftier example in history of artistic genius devoted to the service of religion than we find in Johann Sebastian Bach. He always felt that his life was consecrated to God, to the honor of the Church and the well being of men.”[13]

—–

For those who want more of Bach – whose “melody never grows old. It remains ever fair and young, like Nature, from which it is derived”[14] — here is the well known Toccata and Fugue in D Minor on organ.

[1] Hans David and Arthur Mendel, The New Bach Reader: A Life of Johann Sebastian Bach in Letters and Documents, p. 240, quoted in Gregory Wilbur, Glory and Honor, The Musical and Artistic Legacy of Johann Sebastian Bach, p. 96.

[2] Gregory Wilbur, Glory and Honor, p. 90.

[3] Ibid., p. 1.

[4] David and Mendel, p. 57,quoted in Wilbur, p. 36.

[5] Ibid., p. 225.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Christoph Wolff, Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician, p. 335, quoted in Wilbur, p. 112.

[8] Ibid., p. 222

[9] Ibid.

[10] Otto Bettmann, Johann Sebastian Bach: As His World Knew Him, quoted in Wilbur, p. 222.

[11] Wilbur, p. 224.

[12] Quoted in Wilbur, p. 186.

[13] Quoted in Wilbur, p. 118.

[14] David and Mendel, p. 448, quoted in Wilbur, p. 235.

PF UNIVERSITY

The courses offered by the Providence Foundation Biblical Worldview University (BWU) are designed to equip leaders of education, business, and politics to transform their culture for Christ, and to train all citizens how to disciple nations.

DONATE

Support Providence Foundation today! Choose Minuteman, Patriot, or Founder level and make a monthly impact. Or select ‘Custom’ to contribute now. Join us in shaping our nation’s future