Inventor of the Telegraph (1832)

Samuel F. B. Morse invented the telegraph in 1832 and worked during the next decade to improve it. The first inter-city line was tested in 1844, when a message was sent from the Capitol Building in Washington to Baltimore.

The invention of the telegraph was one of the most significant technological discoveries in history. It ranks with the printing press in its impact in the area of communication. The message from Washington to Baltimore took a few minutes, which before would have taken about a day. When cables were laid across the Atlantic and across the continent, messages that would have taken days and weeks, now took just a moment.

The New York Herald declared Morse’s telegraph “is not only an era in the transmission of intelligence, but it has originated in the mind … a new species of consciousness.” Another paper concluded that the telegraph is “unquestionably the greatest invention of the age.”[1]

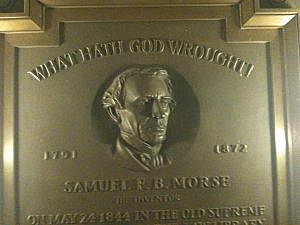

Morse was a Christian who believed he had been chosen by God to invent the telegraph and, for the first time, harness the use of electricity. This discovery would contribute greatly to the advancement of man and the fulfilling of God’s purpose for mankind. Annie Ellsworth, a friend of Morse’s, composed the first message sent over the Washington-Baltimore line on May 24, 1844. She “selected a sentence from a prophecy of the ancient soothsayer Balaam” — “What hath God wrought!”[2] Of this message Morse wrote:

Plaque in the U.S. Capitol commemorating Morse’s invention with the words transmitted: “What Hath God Wrought.”

Nothing could have been more appropriate than this devout exclamation, at such an event, when an invention which creates such wonder, and about which there has been so much scepticism, is taken from the land of visions, and becomes a reality.[3]

Morse considered it remarkable that he, an artist, “should have been chosen to be one of those to reveal the meaning of electricity to man! How wonderful that he should have been selected to become a teacher in the art of controlling the intriguing ‘fluid’ which had been known from the days when the Greeks magnetized amber, but which had never before been turned to the ends of common man! ‘What hath God wrought!’ As Jehovah had wrought through Israel, God now wrought through him.”[4] Morse wrote to his brother:

That sentence of Annie Ellsworth’s was divinely indited, for it is in my thoughts day and night. “What hath God wrought!” It is His work, and He alone could have carried me thus far through all my trials and enabled me to triumph over the obstacles, physical and moral, which opposed me.

“Not unto us, not unto us, but to Thy name, O Lord, be all the praise.”

I begin to fear now the effects of public favor, lest it should kindle that pride of heart and self-sufficiency which dwells

in my own as well as in others’ breasts, and which, alas! is so ready to be inflamed by the slightest spark of praise. I do indeed feel gratified, and it is right I should rejoice with fear, and I desire that a sense of dependence upon and increased obligation to the Giver of every good and perfect gift may keep me humble and circumspect.[5]

Morse would remark in a speech many years later:

If not a sparrow falls to the ground without a definite purpose in the plans of infinite wisdom, can the creation of an instrumentality, so vitally affecting the interests of the whole human race, have an origin less humble than the Father of every good and perfect gift? I am sure I have the sympathy of such an assembly as is here gathered, if in all humility and in the sincerity of a grateful heart, I use the words of inspiration in ascribing honor and praise to him to whom first of all and most of all it is pre-eminently due. “Not unto us, not unto us, but to God be all the glory.” Not what hath man, but “What hath God wrought!”[6]

[1] Carleton Mabee, The American Leonardo, A Life of Samuel F. B. Morse, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1943, p. 279.

[2] Ibid., p. 275.

[3] Ibid., p. 276.

[4] Ibid., p. 280.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid., p. 369.