He brought sight to millions who were blind.

Stephen McDowell

We have a calling in life. It is a divine calling. We are first called to God, to become His child and part of His family. Next we have a calling in the earth as part of mankind’s mission to rule or take dominion over the earth (Gen. 1:26-28). The amelioration of mankind is part of this cultural mandate; that is, we are to work to elevate mankind, to bring advancement to man and make his life better. God gives us unique gifts and skills to help us accomplish our unique task in life.

Os Guinness defines calling as “the truth that God calls us to himself so decisively that everything we are, everything we do, and everything we have is invested with a special devotion and dynamism lived out as a response to his summons and service.”[i] The call of God impacts all areas of life and work, not just our religious life. Fulfilling our calling requires us to discover truth through sciences, apply truth through technology, interpret truth through humanities, implement truth through commerce and social action, transmit truth through education and arts, and preserve truth through government and law.

Historically, Christians have led the way in each of these areas. As these men and women have been faithful to fulfill the call on their lives and utilize the talents God gave them, they have contributed greatly in taking dominion over the earth and extending God’s purposes and government in this world.[ii] The people that God has used have come from diverse backgrounds and many, like Louis Braille, had to overcome great obstacles. But they all embraced their calling and persevered.

The Story of Louis Braille

Even as a blind boy, Louis Braille felt called for a purpose. God had a mission for him. His mission was to make it possible for blind people all over the world to have their own books and their own libraries. These books would bring light to the dark eyes of the blind. He had experienced this darkness for most of his life.

When this mission was growing in his mind, it seemed a remote dream since most blind persons were ignored or looked down upon by society. Through history past, the blind stumbled through life generally alone on a terrifying road. Some shelters were built for the blind by Christians as early as the 4th century, and medieval convents and monasteries usually had an almshouse for unfortunate people. However, most blind did not benefit from this charity. Many were locked up in mental institutions and some used as freak show attractions. Most wandered on their own in the streets. Some were used by con artists to collect hand-outs in the streets, promising to provide for them through these collections but pocketing most of the money for their own use. The blind were cut off from education, apprenticeship, job training, and any sort of normal life. They lived in darkness, not only physical but also mental, having little opportunity to gain knowledge.

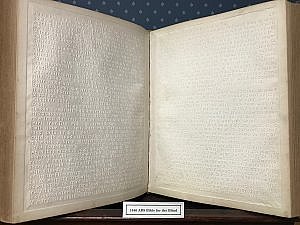

When Louis was a boy there was one school for the blind in Paris that had been started by Valentin Hauy some years before. While it provided useful verbal instruction in the academic disciplines as well as training in music, it was very limited in self-teaching tools for the blind. The school only had three books that the blind could “read.” These large volumes contained pages of raised letters in Latin. The books could only have short discourses since each page could only contain a few sentences, and it took great time and effort for the blind to “read” them.

As a boy, Louis hoped someone would come up with a way for the blind “to see.” But there seemed to be no one. God inspired him with a vision. The Scripture became a source of inspiration. He remembered the words spoken by Father Palluy from the book of Genesis, the first chapter: “Then God said, Let there be light; and the light began.” Louis thought that God surely wanted the light to shine for everyone, even those who lived in physical darkness.

His Life

Louis Braille was born in the small village of Coupvray, France, some 20 miles east of Paris, in 1809. As devout Catholics, his parents had him baptized, hoping to keep him protected from all the dangers that existed for youth in the world at this time.

His father produced all kinds of leather goods in his local harness shop. When Louis was three years old he accidently jabbed an awl in his eye when he was trying to punch a hole in a leather strap in his father’s workshop. The cut became infected and spread to his other eye, blinding him in both eyes. Over time he learned to not only get around his family’s house and yard with the help of a cane, but could travel by himself to the nearby village. His heightened senses enabled him to learn much about his small world. Louis had an insatiable desire to learn; he even wanted go to school like the other boys and girls, but how could a blind boy keep up with those who could see?

With the encouragement of his family and the local Catholic priest, Father Jacques Palluy, Louis entered the local school and quickly excelled. While learning many things, Louis still could not read any of the books in the school or in the church library. Father Palluy gave him a book, whose pages Louis would often feel, but what he earnestly wanted was to be able to read a book on his own instead of having to ask his sister or parents to read to him. But how could he who was blind ever be able to read?

One day Father Palluy came to visit Louis and answered that question. He had learned of a school for the blind in Paris that had developed a way for the blind to read. They had books designed for that purpose. And he would help him enroll and get a scholarship.

At age ten, Louis was the youngest student at the National Institute for Blind Youth, but he quickly excelled. Yet, he had to wait one year before he was allowed to “read” one of the three books for the blind that were in the library. It did not take him long to read these and a few other available pamphlets. While better than not being able to read at all, the technique then in use was slow and very limiting. Large raised letters of the Latin alphabet used by those who could see only lifted the darkness a little for the blind. Louis thought there must be a better way.

He hoped the leader of the school, a professor, or someone would invent a new system of reading for the blind. None of those who could see had a vision to do so. As Louis pondered this hope, he began to think that perhaps he could be the one to fulfill the dream that he believed God put in his heart. But he was only a teenager. How he could accomplish what others older and wiser than he had not?

His desire to read books like other youth only grew. He could not escape the vision. There was work that needed to be done. He would seek to fulfill the mission of God. He would do all he could to make it possible for blind people everywhere to have their own books and their own libraries. He would make his life count and find a way to enable the blind to have books. He would help bring great light to those who lived in darkness. He would seek to fulfill his calling.

Finding a solution was not easy. He pondered it day and night. The fingers were the eyes of the blind. The few books he had read were by feeling raised letters on paper. But this was slow, and the blind could not write using this method, so it was very limiting. How could he produce an alphabet that would enable the blind to quickly and easily read with their fingers but also write to others? He experimented with many things, looking for a code.

Help came when he learned that a Captain Barbier had invented a code during the war that soldiers used in the dark to communicate with one another. His system of “night-writing,” called sonography, enabled orders to be sent that could be read with the fingers without use of any light, which might alert the enemy.

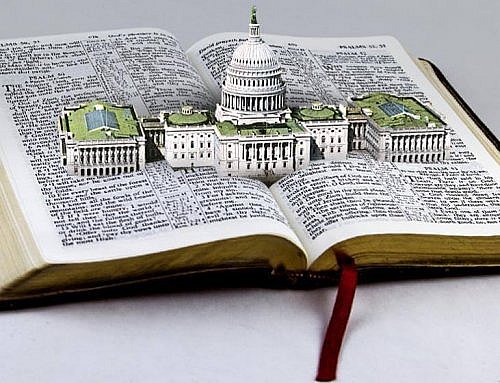

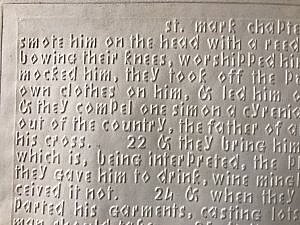

A raised letter Bible open to the Gospel of Mark. “Reading” the raised words of regular English lettering was slow and required large letters. This was before the Braille system was widely accepted.

Unfortunately, Barbier’s “night-writing” was very limiting as it was based upon sounds, not letters, and used a pattern of dashes and dots that were rather complex, and hence was useful to send only simple messages. But it helped point Louis in the right direction.

In the months that followed, Louis worked on devising a code that the blind could use to read and write. It consumed his spare time, while at school in Paris or during the summer break at home in Coupvray. He carried with him a writing board and pointed tool where he could make pinpricks on paper, experimenting with hundreds of combinations of dots and dashes. His fingers became extremely sensitive, able to “read” with the slightest touch.

He patiently endured failure after failure, often forgetting to eat as he worked on the problem. A new code began to emerge where each letter could fit under the fingertips, thus enabling him to move quickly across the page, just as the eyes move along reading sentences. After three years of almost constant effort, he finally developed a system that worked well. He could write pages quickly and easily and read them back with his fingers, just about as fast as eyes can read.

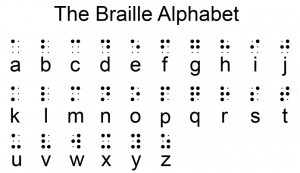

While over the years he would make some changes to improve his code (he removed use of dashes for dots only), the basics were there. The code, which would later be called Braille in honor of the inventor, was based upon a tiny cell of six raised dots that was two lines wide and three lines deep.

1 . . 4

2 . . 5

3 . . 6

Each letter had a unique raised dot pattern within this cell, as seen here:

Louis, a fifteen-year-old boy, had created a system of reading for the blind that would one day rank him as one of the greatest of inventors. Yet, as is often the case with inventions, it would take many years before this light-giving tool would be recognized and used on a wide scale. In fact, Louis would see limited use of his Braille system during his life. Many even worked against the dispersal of his code.

Some teachers at the school for the blind resisted implementing the Braille dot system because it would require them to learn the method in place of how they had been teaching for years. The French Ministry of the Interior stated the government favored no changes at the school. Consequently the administrators of the Institute worried if they did embrace Braille’s dots they may lose their government funding and would have to rely on meager donations. The leader of the Institute for the Blind, Dr. Pignier, was supportive of Louis and his dots, but said they “will have to go on teaching the embossed-letter reading until we have permission otherwise from the government.”[iii]

While Louis fought for use of his method, he continued his studies in all areas, especially music, in particular the organ. He became so proficient he was praised by noted composer Felix Mendelssohn and was hired as the organist at a nearby small church. In accepting the meager-paying job, he was showing a blind person could hold a position of importance.

At age 19 he was chosen to be an apprentice teacher at his school, the first blind student to be hired. During this time he began work on a book that explained his six-dot cell method of teaching reading and writing. It would be written using his dot cell alphabet, and hence readable by blind as well as those with sight, and was entitled: Method of Writing Words, Music and Plain Songs by Means of Dots, for Use by the Blind and Arranged for Them.

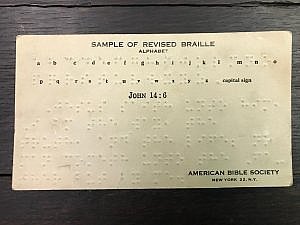

The American Bible Society published this card for the blind containing the Braille alphabet and the Scripture verse John 14:6.

He hoped it would help sway the government and others to embrace his system. But year after year the government rejected Dr. Pignier’s requests to make the dot system the official method of reading and writing at the Institute. Louis’ system would be able to save almost any blind person from being ignorant, but few could see its importance.

Some of those few who strongly embraced the Braille system were the blind students at the Institute. At age 25 Louis was appointed to a professorship at the Institute, along with two other blind teachers. (He taught at the Royal Institution from 1834 to 1839.) All three used the dot cell method and the students excelled. Louis himself increased his reading speed up to 2500 dots per minute.

Over time Braille and his students were able to give demonstrations of rapid reading and writing with the dot system, which brought much praise, even from the French King Louis Philippe. Even so, most still could not see the great importance of Braille’s invention.

In his 30s, Louis was diagnosed with consumption (likely tuberculosis), which had been afflicting him for many years and would take his life in his prime years. Yet even with declining health, he continued to fight for his dot-system against those who opposed it. One of those men, Dr. Armand Dufau, was appointed the new director at the institute where Louis taught. He directed that the Braille dot-system not be used in the classrooms. Even more devastating, Dr. Dufau ordered all of the books that Louis had transcribed into dots to be burned. But Louis relied on God and continued in his calling.

Louis and his students protested and remained resolute until Dr. Dufau reversed his position on banning the Braille code. Their continued efforts eventually brought about acceptance of the Braille method in the school of the blind, and much later in France and nations around the world. They also helped open the Institute to girls for the first time.

Louis went on to invent, with another blind man Pierre Foucault, a machine that would print raised dots on paper. This printing method, called raphigraphy, enabled the blind to read and write any- thing. Blind and sighted persons could now send messages that both could read. This machine was a primitive version of the typewriter.

Although it was slow, Braille’s dot-system gradually spread. It would forever change the life of the blind. No matter how many obstacles got in his way, Louis acted upon his life mission, his calling. He could see the forest in the seed, while most people could not. In his short life he saw small advances in the use of his dot-system, but it would take generations for Braille’s work to have its fullest impact. Louis never lost heart. Likewise, we should continue to pursue the call of God on our lives. God calls. We obey. He brings the increase in His time, which is often not as we hope or expect. As with Louis, when God calls us, we can have faith that he will provide, naturally or supernaturally, everything needed to accomplish the mission.[iv]

Throughout his life, Louis Braille was provided all he needed to accomplish his calling: the friendship and guidance of a minister, loving and supportive parents, a scholarship to the blind school, a role as teacher and professor, and contacts with many influential people.

Tuberculosis eventually took Braille’s life at age 43. His Christian faith remained evident on his deathbed. To lamenting friends he said: “Please do not fear for me. I am quite content. God simply must be telling me that my work here is finished.”[v] As the end approached he asked to receive Holy Communion. He is reported to have said: “God was pleased to hold before my eyes the dazzling splendours of eternal hope. After that, doesn’t it seem that nothing more could keep me bound to the earth?”[vi]

He died on January 6, 1852, two days after his 43rd birthday, having fulfilled his calling. A friend, Hippolyte Coltat, later entered in his diary: “Louis Braille [had] delivered up his pure soul to the hands of God.”[vii] Louis was buried in a simple grave in his hometown at Coupvray. Little notice was taken of the death of Louis Braille because his invention had not yet spread widely. This has been true of many other creators and inventors. It would take many decades for the world to see the significance of his work.

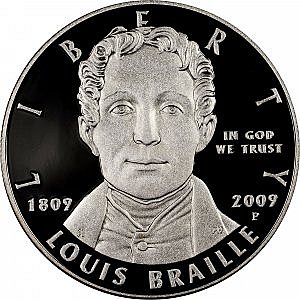

The Louis Braille commemorative U.S. silver dollar was released in 2009 and has readable braille on the back.

After his death a few crusaders produced the Lord’s Prayer in dots in five different languages. The Book of Psalms was printed in the six-dot type facings, and prayer books were produced to be used for chapel services. The Scottish missionary to China, W.H. Murray, used the Braille system to translate writings into Chinese so the blind there could read. Over time the American Bible Society produced the Bible in Braille in dozens of languages.

Today the Braille system is accepted as the universal language by which the blind can read and write. A great variety of books are now available in Braille. It took over 100 years, but on June 20, 1952, France honored her influential son by removing Louis Braille’s body from the simple grave in Coupvray and reinterring it in the Pantheon in Paris. This man who could not see is now universally recognized for bringing light and “sight” to millions who are blind. The impact of his fulfilled calling will continue for generations.

End Notes

[i] Os Guinness, The Call, Finding and Fulfilling the Central Purpose of Your Life, Nashville: Word Publishing, 1998.

[ii] For scores of examples see, Stephen McDowell, Transforming Nations through Biblical Work, Charlottesville: Providence Foundation, 2018.

[iii] Anne E. Neimark, Touch of Light, The Story of Louis Braille, New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc., 1970, p. 141. This is one of innumerable examples supportive of keeping government out of education.

[iv] There are many such examples in the Bible. For example, as Jesus approached Jerusalem just prior to His crucifixion he told His disciples to go into the nearby village and they would find a colt that they were to bring to Him (Matt. 21), and if anyone questioned them they were to say the Lord had need of it. Here was a supernatural provision for the fulfillment of prophecy and Christ’s mission. Jesus even provided for unjust government taxes in a supernatural way, telling Peter he would find a coin in the mouth of a fish (Matt. 17:27).

[v] Neimark, p. 176.

[vi] https://www.christiantoday.com/article/blind-but-now-i-see-the-christian-legacy-of-louis-braille/122911.htm

[vii] Neimark, p. 178